England's Peterloo Massacre victims and their shocking stories

5-6 minute read

By Alex Cox | August 16, 2019

Relive harrowing blow-by-blow accounts of how lives were lost at the Peterloo Massacre of 1819.

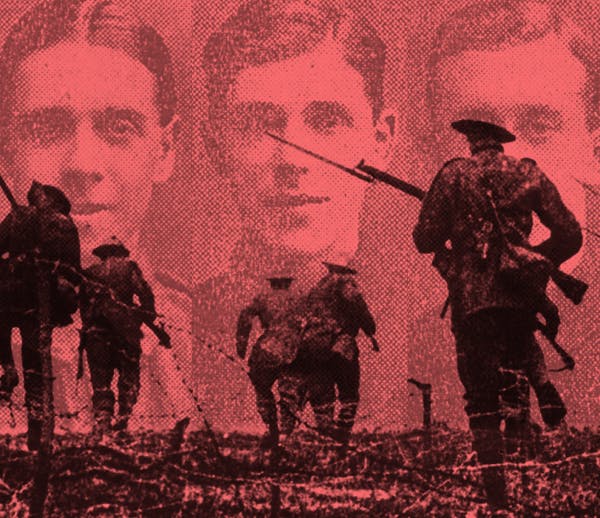

The Peterloo Massacre took place when army cavalry charged a crowd of 60,000 plus protestors in Manchester, England on August 16 1819. Around 18 people were killed and upwards of 400 were injured in the incident, making Peterloo one of the most horrific cases of mass brutality to ever take place on British soil.

What caused the Peterloo Massacre?

In the years directly following the Napoleonic Wars, a combination of famine and widespread unemployment led to a drive for political reform in Northern England. A peaceful rally was organised by the Manchester Patriotic Union, led by Henry Hunt. At the demonstration the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry were instructed to disperse the crowd but did so violently with their weapons drawn. The fatalities occurred in the ensuing melee. The massacre is sometimes dubbed the Battle of Peterloo because it took place on St. Peter’s Field just four years after the famous Battle of Waterloo.

A special collection of Findmypast records detail the witnesses and casualties who were involved that fateful day in Manchester. Here are their traumatic stories.

The Waterloo veteran

Ironically, John Lees served at the Battle of Waterloo. His military record shows he was a wagon driver in the Royal Artillery. During Peterloo, Lees survived the initial attack by the Yeomanry but died weeks later from his injuries.

Before his death, it’s claimed Lees told a friend:

"“At Waterloo there was man to man but here it was murder.”"

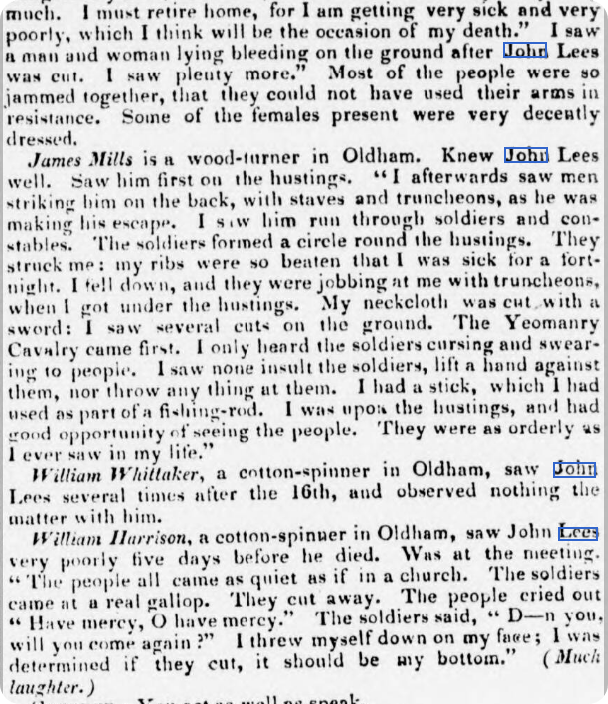

One of hundreds of articles about John Lees' inquest in our newspaper archive

As an army veteran, he was the only victim to receive a full inquest into his death but after interference from the authorities, no verdict was returned.

The standard bearer

41-year-old weaver and member of the Saddleworth, Lees and Mossley Union, John Ashton died at Peterloo after being sabred and trampled to death by the crowd.

The father of one carried a black banner at the rally inscribed with words;

""Taxation without representation is unjust and tyrannical. NO CORN LAWS.""

Undoubtedly, this made him an easy target for the cavalry.

The innocent child

The first fatality of the day was also the youngest. Two-year-old William Fildes was killed after his mother, Mrs Anne Fildes was trampled by a horse while carrying him in her arms. In a most unfortunate turn of events, Mrs Fildes wasn’t even part of the protest. She was caught up in the unrest while running errands.

The constable killed in revenge

As rioting continued around the city, a 1,000 strong mob descended on the Mill Street home of Robert Campbell, one of the special constables brought in by the magistrates to police the assembly. As they chanted “villain” and “kill him” outside his window, Campbell fired a pistol from the upstairs window and attempted to flee but the mob caught up, dragged him into the street and beat him to death.

The constable killed by friendly fire

50-year-old Thomas John Ashworth was Landlord of the Bulls Head Inn in Marketplace, Manchester. Sworn in as one of 400 special constables by Magistrates (prior to the formation of the Police Force) to assist in policing the public meeting on Peter’s Fields, he was mistakenly cut down with a sabre by one of his own and trampled to death by the panicked crowd.

The teenagers who fought back

16-year-old William Bradshaw of Lilly Hill joined the throngs of angry protestors who began rioting in New Cross once word of the massacre began to spread. When the rioters began attacking a grocer's shop, the soldiers opened fire striking at least four members of the crowd, one of whom was Bradshaw. He died at the scene.

17-year-old Joseph Whitworth was also part of the same revolting crowd. Despite being struck in the back of the head by a musket ball, he survived for four days before dying in Manchester’s Royal Infirmary on 20 August.

The bayoneted gardener

62-year-old Gardener Thomas Buckley was described by his neighbours as a;

"“person fanciful to the fruit garden, a staunch patriot, an enemy to oppression.”"

He was bayoneted and slashed by a sabre during Peterloo but did not die from his wounds until 1 November that year.

The pregnant mother of six

Mary Heyes of Chortlon Row was a 44-year-old, pregnant with her seventh child. She was trampled by a horse on the field and sustained injuries that left her severely disabled. The stress placed on her body caused her to go into early labour on 17 December 1819 and she died as a result. Her premature baby survived.

The cellar casualty

While fleeing St Peter’s Field, 38-year-old Martha Partington was either thrown or fell into a cellar. During the crush, more panicked victims either fell or jumped down the cellar steps to escape and she was crushed to death. Her husband and two children were awarded just £5, roughly £430 today, in relief.

The dyer trampled to death

41-year-old James Crompton of Barton-upon-Irwell was trampled by horses and died in late August from his wounds. Little is known about his life but records suggest he worked as a dyer and was unmarried without children.

The father denied justice

David Dawson, the father of 19-year old victim Edmund, submitted two petitions seeking justice after his son’s murder. However, his death was covered up. At the coroner’s inquest, while the jury agreed Edmund had died from a head wound caused by a sabre or other sharp instrument;

"“how such a wound was given no satisfactory evidence was adduced.”"

The man who was dissected and demeaned

22-year-old John Rhodes died three months after he was horrifically injured at Peterloo. After his death, Rhodes's body was dissected by order of the local magistrates who wished to prove that his death was not a result of the massacre. Unsurprisingly, the coroner's inquest found that he had died from "natural causes" and his father received just over £6 (roughly £350 today) in compensation.

The weaver imprisoned without trial

Arthur O’Neill, a weaver of Pigeon Street, was badly beaten about the head by constables before being trampled by the stampeding crowd. According to his widow Sarah, he was captured and imprisoned for five months without trial or bail before being released in December. He died three weeks later on 1 January 1820.

The hastily buried

42-year-old cotton spinner, Samuel Hall was cut on the temple by a sabre and trampled by horses. He was carried straight to the infirmary where he died three weeks later and was quickly buried in Hulme without a coroner’s inquest.

The unborn child whose mother was imprisoned without trial

Despite being heavily pregnant, prominent rally member Elizabeth Gaunt was brutalised by constables after she was found hiding from them. She was held in solitary confinement for 11 days without trial, received no medical attention and was also barred from seeing her husband. Elizabeth miscarried as a result of her treatment.

The key player killed by her neighbour?

Sarah Jones helped erect the hustings and gave a warm-up speech for Henry Hunt at the rally. It’s claimed she knew the special constable who apprehended her, a neighbour Thomas Wordsworth, and was able to identify him by name. A year later she was listed as “still unwell” by the relief committee and was dead within three years.

The mystery woman?

Margaret Downes is perhaps the most puzzling victim of the massacre. Very little is known about her or her eventual fate. While Downes’ death has not been 100% verified, it was reported that she was;

"“secreted clandestinely and not heard of since, supposed dead”"

Some historians think the authorities realized how damaging news of such grievous wounds being inflicted on a woman would be and covered it up.

The constable crushed to death

William Evans, another special constable sworn in by the magistrates, was a carter by trade. In a cruel twist of fate, he was trampled to death by the very same horses he worked with after losing his footing in the chaos. He was reported as being in a “dying state from crushes and internal bruises” in December that year.