Here's what it was like to take a national census back in 1921

7-8 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | October 11, 2022

From organizing the enumerators to producing the reports, collecting the 1921 Census of England & Wales was an epic undertaking. Stephen Rigden explains how it was done and why it’s so important.

The Census Act of 1920 put the census of England & Wales on a permanent footing and enabled not just the 1921 Census but all future censuses to be taken. Before then, the census apparatus had to be created anew before each census could be taken.

From then on, the Census Office was a permanent part of the General Register Office, which was based in the north wing of Somerset House on the Strand in London.

Somerset House, London, 1895. View full-size in the Francis Frith Collection.

For 1921 Census operations, the Census Office took over the old Lambeth Union Workhouse in Prince’s Road (renamed Black Prince Road in 1939).

Preparing for the 1921 Census

One of the first steps in the taking of the census is to divide up the country into manageable units – enumeration districts – each of which could be covered by a single person – the enumerator – in the course of a day. In urban areas, this might mean 300 or more households in just a handful of neighboring streets. In rural areas, however, the enumerator might be expected to cover, on foot or by bicycle, a route of, say, five miles, visiting all the hamlets, isolated cottages, and farmsteads within their enumeration district.

The position of enumerator was a short-term contract. Enumerators were engaged only for a period of a few weeks before and after census night. Most would have been teachers, office clerks, and other literate and numerate individuals. Others were ex-servicemen – and of course, in 1921 the teachers and office clerks could well have been veterans of the Great War too.

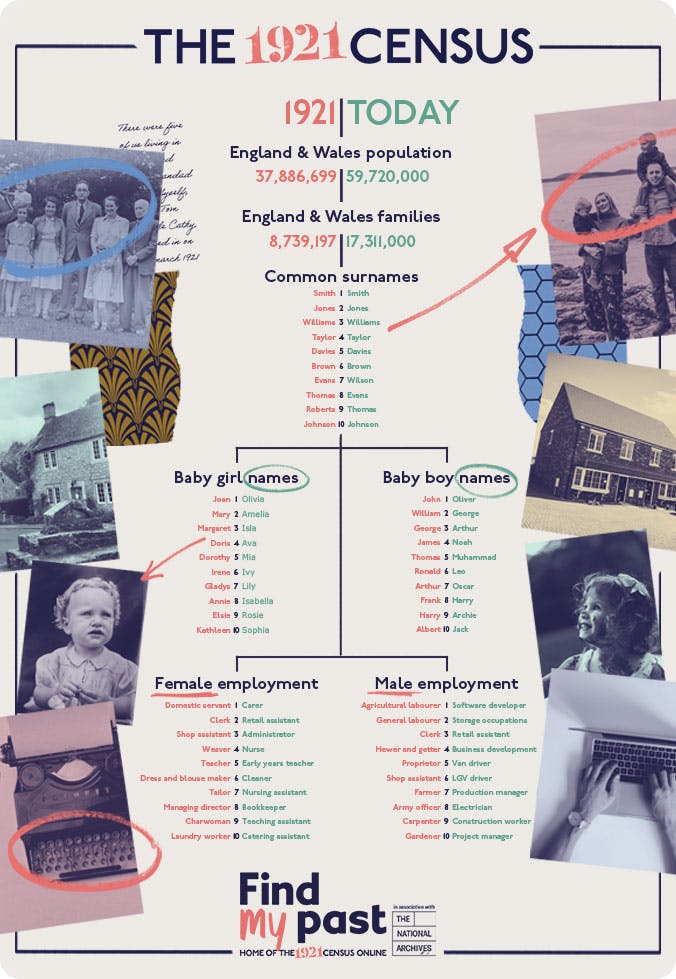

Discover 1921 versus 2021. View in more detail here.

Before the census, the enumerator had to identify all the households within their enumeration district and address a census schedule (the familiar census return or form) for each one.

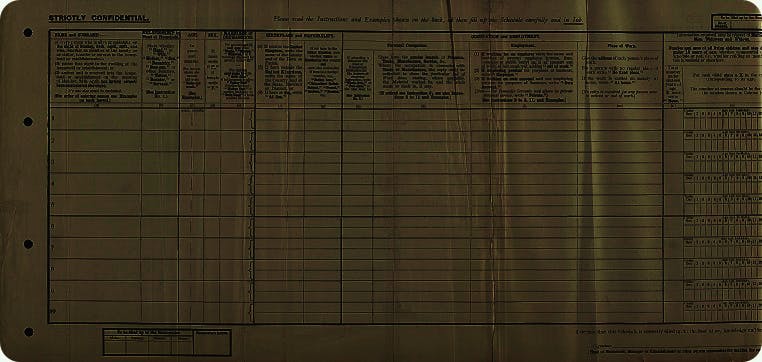

The blank form our ancestors were asked to complete in 1921.

A household was defined as an independent unit. For example, if there was a family living upstairs and a family downstairs in a two-story terraced house, each was a separate household and needed its own census schedule.

A boarder – an individual who received both bed and board within the family – was part of the household in which he or she boarded. On the other hand, a lodger – an individual who received bed only, and ate independently of their hosts – constituted their own household and required their own census schedule.

On the front of each census form, the enumerator wrote the name and address of the householder responsible for completing and returning the schedule. The enumerator also had to write the registration district, registration sub-district, and enumeration district number. Some enterprising enumerators seem to have invested in bespoke rubber stamps to spare themselves the tedious task of writing out the same text hundreds of times. An alternative explanation is that the rubber stamp was the handiwork of the next official up within the hierarchy – the sub-district registrar.

The boundaries of the enumeration districts had been set earlier and defined by the so-called plans of division. An enumerator was appointed for each one – 38,563 in total – and supplied with a stack of blank schedules believed to be appropriate to the task at hand.

Then, between June 11 and 18, 1921 the enumerators went around their enumeration districts and distributed the census schedules according to need and availability. A household in England with a headcount of up to 10 would receive the standard schedule type code E form. A larger household of 11 or more occupants would be given the next size up, being the schedule type code EE. If the enumerators ran out of Es, EEs were given out to smaller households.

Each schedule was folded in four so that the address panel appeared on the front. This may have been done for ease of posting through letterboxes, or simply for the convenience of carrying around the district if enumerators handed them to householders personally, while giving instructions on how to fill in the form, answering any questions, and reminding them when they would return to collect the completed form.

Taking the 1921 Census

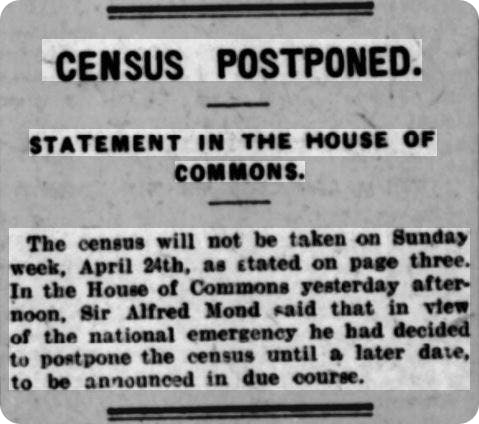

The householder wrote in the personal particulars of each individual staying overnight in the household on Sunday, June 19, 1921. You will see that this is not the date printed on the census schedules (which is April 24, 1921).

The census was postponed from its originally intended April date because of industrial action. Coal miners were on strike and there was the prospect – later averted – of a national strike (involving transport workers) which led Lloyd George to call a state of emergency on April 5, 1921, which mobilized the Army Reserve and a new Defence Force from April 8.

Runcorn Weekly News, April 15, 1921. Read the full article.

The Census Office did not want to delay the taking of the census beyond June. If it were to do so, it would run into vacation season, which would distort the picture of population distribution. Whole factories in towns such as Bolton and Salford might close and workers decamp to seaside resorts such as Blackpool or Prestatyn, producing misleading figures for the statisticians.

Vacation scenes along the coast in East Sussex, 1921. View full-size in the Findmypast Photo Collection.

Similarly, university students would break up for the summer vacation, and harvest season with its associated migrant labor flows would begin. Accordingly, unwilling to postpone further, the Census Office pressed ahead with the census on June 19, 1921. The millions of forms printed for the intended April census were used rather than pulped.

Although very precise instructions, both printed and verbal, on how to complete a form were given, many still completed it differently. For example, there is an instruction to fill in the form in ink. Some householders did complete their schedules in blue or black ink, using fountain pens or dip pens. But others used indelible or laundry pencils, and others graphite or colored pencil.

Some householders misunderstood what was required in recording the number and ages of children and in which row (it should have been against a husband and not additionally against his wife, for example). The child dependency grid on the right-hand side of the back of the schedule, where an X was meant to be entered against age for each child and step-child up to and including 15 years, was often a mess and had to be redone by an irritated enumerator or census officer.

From June 20, 1921, the enumerators returned to their enumeration district and started collecting the completed census schedules. You can imagine that there would not have been a single problem-free trip. Some householders would not have been in when the enumerator knocked. Some might not have been cooperative. Some might have filled in the schedule incorrectly, or have questions in need of answers, or concerns about the uses to which the asked-for information would be put – would it be used for conscription, for example?

Peterborough Standard, June 25, 1921. Read the full article.

You can imagine the enumerators having to make repeated excursions around their assigned district before they had gathered up all the schedules. It is at this point, we think, that the enumerators sorted the census schedules into a tidy and sensible order and numbered them in the Schedule Number box on the back of the form. It's possible that schedule numbering was done before distributing the forms. If so, there would have been the risk that households might move from or arrive at a property in the final days before census night, upsetting the schedule number order.

Collating the census data

By June 27, the enumerators should have checked and bundled up the census forms and taken them to the sub-district registrars, who would be expecting deliveries from all the enumerators for the enumeration districts within their registration sub-districts. Further checking was done at this point and queries were raised with enumerators, and presumably also by enumerators with some householders at the instruction of the registrars. Only then were the sub-district registrars comfortable sending all the schedules for all their enumeration districts further up the chain, where they reached the Census Office in Lambeth.

The Census Office had a workforce of 550 at its peak in August 1922. This was made up of a relatively small number of permanent employees and a much larger number of contract workers brought in for the enormous task of processing the schedules.

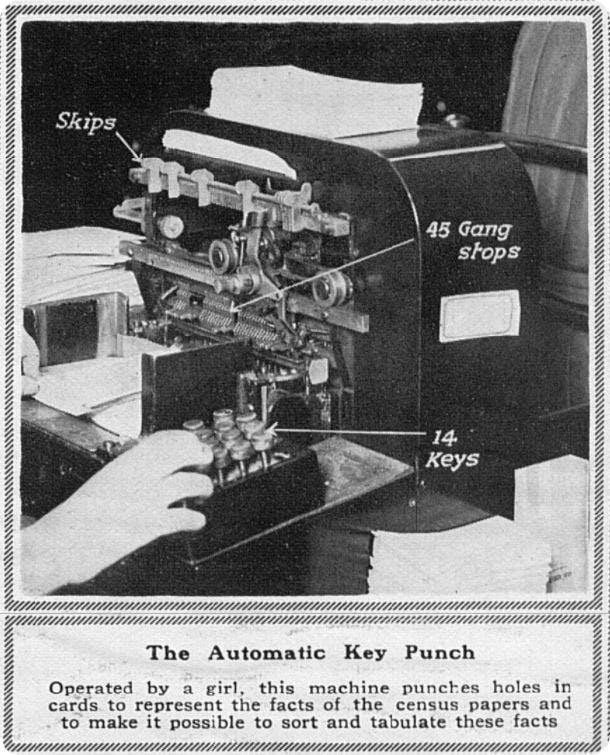

Like the 1911 Census before it, the 1921 Census used sophisticated, mechanized data-processing instead of the old clerical “tick and table” methods of the 1841 to 1901 Censuses. The largest cohort of staff employed were the 202 punchers or punch-card girls. These were 15- to 17-year-old girls with manual dexterity who operated the machines that punched holes in tabulation cards to record coded information about each individual. These cards then went through separate sorting and counting machines to produce the tabulated raw data of interest to the statisticians and demographers of the Census Office. 37,886,699 cards were produced – one for every person enumerated in the 1921 Census.

The Sphere, April 16, 1921. Read the full article.

Before the census schedules reached the punch-card girls, however, each one was examined by a clerical officer who made annotations in a distinctive green ink. Presumably, green was chosen as a color it was thought unlikely that householders would use it when filling in their forms. Principal among the green-ink annotations is the coding of occupation, but you may see others in different parts of the forms.

On schedules completed in the Welsh language, clerical officers, presumably using Welsh-English language dictionaries, went through and translated text into English using their distinctive green. For example, you are likely to see translations of Welsh-language occupations and kinship terms.

The physical processing of the 1921 Census went on until at least 1923. The Census Office produced a variety of reports on their findings, beginning with a high-level summary Preliminary Report of August 23, 1921, just two months after the census was taken. Then, a series of county-level volumes dating from October 1922 to March 1924 and subject volumes in 1925 were produced. Finally, the definitive General Report was published in 1927.

Most of the temporary staff, such as the punchers, would have been laid off when the job of punching, sorting, and tabulating was done, and presumably, the permanent staff would then have vacated the former workhouse in Lambeth and gone back to the General Register Office’s headquarters at Somerset House.

The original census schedules were bound into hardcovers, producing over 28,000 volumes, and then went into storage. The plans of division were re-visited in the early stages of the preparations for the ill-fated 1931 Census (which was destroyed in 1942 by a fire started accidentally by a dropped cigarette).

The Census Office tweaked its administrative geography for 1931, especially the size and numbering of enumeration districts, in line with changes in population distribution. This is why you can see annotations on the plans of division dated to, for example, 1928. Unfortunately, officials often struck out text that was valid in 1921 and overwrote it with updated text for 1931. As most of these textual alterations are not dated, it’s not always clear whether the marking is a genuine correction dating to 1921 or a subsequent change for 1931.

The 1921 Census of England & Wales has none of the enumeration books that you see in the censuses from 1841 to 1901. Enumeration books were produced by enumerators in 1921 but these were discarded and destroyed at some point. Neither does the 1921 Census have the enumerator summary books included with the 1911 Census, which give just the head of household. Instead, the 1921 Census comprises the original household schedules (as in the 1911 Census) and the plans of division which enabled the Census Office to conduct its work with maximum efficiency during the long summer of 1921.

The 1921 Census has finally arrived online, exclusively at Findmypast. To unlock the mysteries in your family story, all you need to do is subscribe or upgrade to a Premium subscription today. What family secrets and surprises will you discover from the forms your ancestors completed?