The Battle of Jutland: uncovering the stories of our Royal Navy ancestors

9-10 minute read

By Charlotte Ward Kelly | December 22, 2025

Did a member of your family fight in the Battle of Jutland in 1916? Naval expert Charlotte Ward-Kelly delves into Findmypast's exclusive naval records to tell their stories.

As smoke rolled across the North Sea, steel decks trembled under thunderous gunfire and thousands of sailors waited at their posts, unsure if they would see another sunrise. For many families, the Battle of Jutland is not just a chapter in British history, but the moment an ancestor's life was forever changed. With Royal Navy stories now at your fingertips, you can delve deeper and understand their experiences as never before.

The 1916 Battle of Jutland was the largest naval battle of the First World War, and one of the most famous maritime engagements in history. Lasting 12 hours - from 31 May to 1 June - it involved thousands of men and over 250 ships.

The struggle for the seas

At the end of the nineteenth century, Britain and Germany were engaged in a naval arms race. Germany wanted to build a navy that could challenge Britain’s naval supremacy whilst Britain sought to maintain its dominance of the seas.

New technologies, ship designs, and methods of training were introduced during this period. This rivalry continued into the First World War, as a great naval battle seemed imminent.

How did the Battle of Jutland break out?

On 31 May 1916, the German High Seas Fleet under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer attempted to lure a portion of the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet into a trap.

British intelligence had been alerted to this plan, so Britain sent the entire Grand Fleet, as well as at Battle Cruiser Fleet, to meet the German navy in the North Sea.

Although Britain significantly outnumbered the German navy, the outcome of the battle was indecisive. Both sides claimed victory.

Though Britain lost more ships and men (14 ships and 6,000 men vs 11 ships and 2,500 men), Germany still failed in her aim of destroying the British Royal Navy and Britain maintained her dominance of the seas.

The battle was a harrowing experience for sailors on both sides. They witnessed heavy gunfire, torpedo attacks, and close-quarter combat, as well as the sinking of ships and the deaths of shipmates. Smoke and haze from the gunfire made navigation and sight difficult, and crews often had to tackle devastating fires that spread through the ships.

We've delved into our records and uncovered the stories of those who were present at the Battle of Jutland.

Prince Albert

Acting Sub-Lieutenant, HMS Collingwood

Prince Albert ('Bertie'), the second son of George V, joined the navy as a boy. Before Jutland, he was promoted to acting sub-lieutenant on 15 May 1916, serving in HMS Collingwood.

Bertie was present at the Battle of Jutland, and even wrote a detailed account of his experience.

"We went to 'Action Stations' at 4.30 p.m. and saw the Battle Cruisers in action ahead of us on the starboard bow...We opened fire at 5.37 p.m. on some German light cruisers. The 'Collingwood'’s second salvo hit one of them which set her on fire, and sank after two more salvoes were fired into her."

Bertie’s ill health and royal duties meant that he had to leave active duty after Jutland. He would join the Royal Air Force after its formation in 1918 and became the first member of the royal family to qualify as a pilot.

HMS Collingwood, 1912.

His duties as a prince took him away from his military service, and eventually, in 1936, Bertie became King George VI.

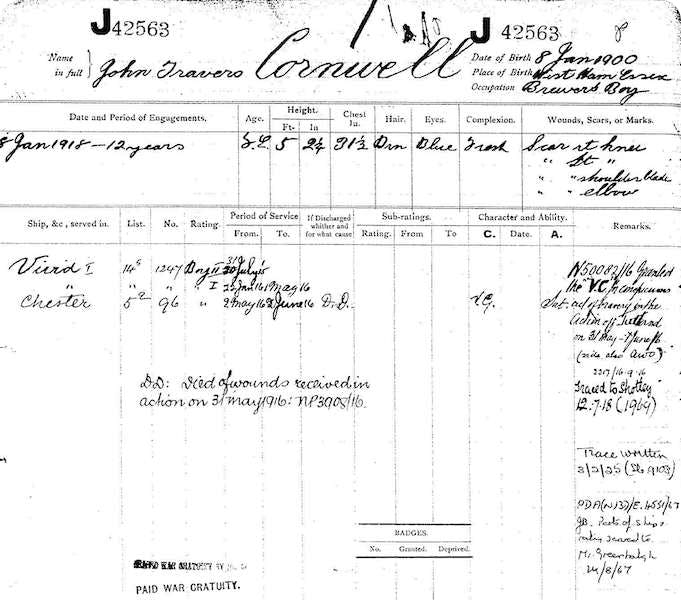

Jack Cornwell

Boy 1st Class, HMS Chester

""Have you news of my boy Jack?”

Not this tide."

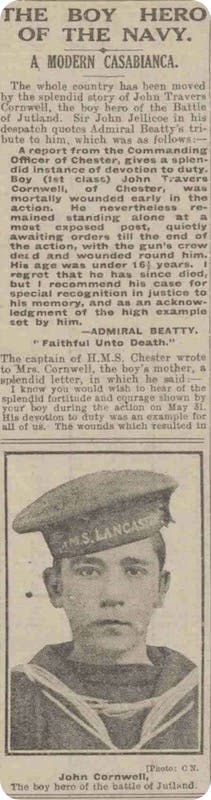

Perhaps one of the most famous participants in the Battle of Jutland, Jack Cornwell, was a Boy 1st Class serving in HMS Chester.

At the age of 15, Jack joined the navy in July 1915. He enjoyed naval life, having been desperate to join when he left school at 13, and did very well in his training. On 1 May 1916, he completed his training and subsequently joined HMS Chester. 30 days later, Jack would go into battle for the first time.

During the battle, HMS Chester came under intense fire. Cornwell was serving on the 5.5-inch gun mounting with other members of the crew. Throughout this engagement, the gun’s crew were killed or mortally wounded. Cornwell, at only 16 years old, was also wounded but was able to continue operating the gun.

After the action, Cornwell was found standing at his gun, shocked and wounded. Chester was ordered home and Cornwell was transferred to Grimsby Hospital where he died on 2 June 1916.

Three months later, Cornwell was recommended for a Victoria Cross which was endorsed by George V. His naval records note that he was ‘granted the VC for conspicuous act of bravery in the action off Jutland’. His mother Lily received Jack’s Victoria Cross from George V on 16 November 1916.

His story was used as propaganda, to inspire bravery amongst the sailors and soldiers still fighting. His family were interviewed about the ‘boy hero of Jutland’ and his story was told and retold in the papers. As there was no photograph of Jack to accompany the stories, one of his brothers was asked to put on one of his uniforms and pose for photographs.

Jack’s story inspired films, art, and poetry, including Rudyard Kipling’s My Boy Jack. 21 September was declared ‘Jack Cornwell Day’ and schools were encouraged to listen to his story and donate a penny towards a ward being set up at the Star and Garter Home for wounded servicemen in Jack’s name.

Tragically, Jack’s father died in October 1916 and his half-brother Arthur was killed in September 1918. The public attention and grief must have been unbearable for Jack’s mother Lily - as she was not legally married to Jack’s father, she did not receive his pension, nor did she get any help from the money raised in Jack’s memory. She died in poverty in October 1919.

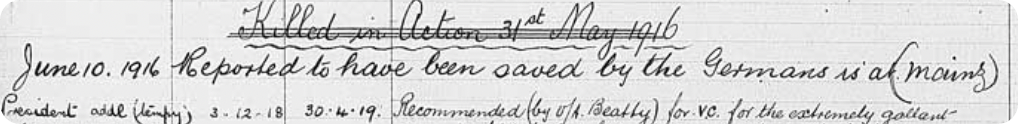

Edward Barry Stewart Bingham

Commander, HMS Nestor

Edward Bingham was born in Bangor Castle in 1881 and was the third son of Lord Clanmorris. Bingham entered the Royal Navy in 1895 following his education and training in HMS Britannia and was confirmed as a sub-lieutenant in March 1901.

At the Battle of Jutland, Bingham was in command of a destroyer division of HMS Nestor (Bingham was on board Nestor), HMS Nomad, and HMS Nicator. In the early evening of 31 May, the British destroyers came under heavy fire. Nomad was badly hit but Nestor and Nicator carried on and engaged the enemy, sinking two ships.

After the German ships disengaged, Bingham ordered Nestor and Nicator to pursue them, despite coming under heavy fire. Nestor was badly damaged and came to a standstill whilst turning away from the enemy. Whilst stuck, the crew were able to fight off a German destroyer.

Despite their efforts, Bingham knew the inevitable was going to happen. He destroyed all confidential paperwork and ordered his men to prepare to abandon ship by launching rafts and gathering supplies like water. German ships continued to fire at Nestor, the crew abandoned ship, and Nestor sank.

In his memoir Falklands, Jutland and the Bight, Bingham described this moment:

Whilst watching her sink, the crew let out cries of 'God Save the King' to pay tribute to Nestor.

Originally reported as killed in action, Bingham and many of his crew were picked up by a German ship and became prisoners of war. During this period, Bingham described that time as dispiriting and irksome but was pleased to see so many from the division alive.

A memorial to Edward Bingham in Kilcooley.

(Image credit: Dean Molyneaux, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14363000)

During his time in Germany, Bingham was awarded a Victoria Cross for the ‘extremely gallant way’ in which he led his division. After the war, Bingham returned home and continued to serve in the Royal Navy, rising to the rank of Rear Admiral. He died in 1939.

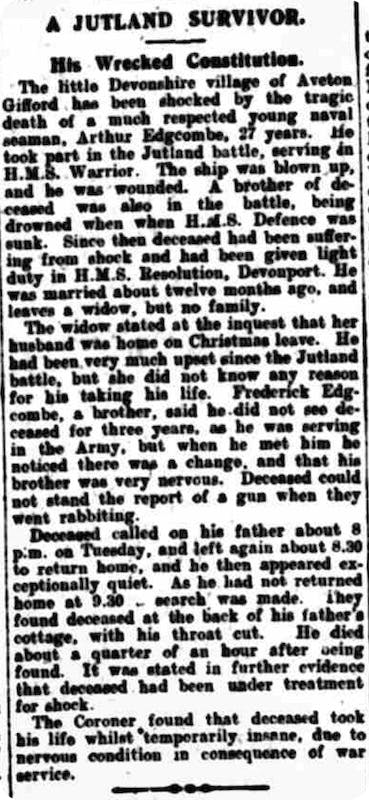

Arthur and Richard Edgcombe

Stokers, HMS Defence and HMS Warrior

Brothers Arthur and Richard Edgcombe were born in Kingsbridge, Devon. With an older brother in the Royal Navy, Arthur and Richard followed the same path and joined the service before World War One broke out. As their service records reveal, Arthur and Richard were stokers in the navy. At the Battle of Jutland, Richard was in HMS Defence and Arthur was in HMS Warrior.

During the battle, Defence was hit several times by German ships leading to her sinking. Richard, along with the rest of the crew of Defence, was killed. Meanwhile, Warrior had also come under heavy fire resulting in large fires, heavy flooding, and a high death toll. As a stoker, Arthur would have been in the chaos of the engine room. Remarkably, Arthur survived the battle.

After the battle, Arthur suffered with shock, so was given light duties in HMS Resolution. When he returned home on leave for Christmas 1919, his wife and brother noted that he had been upset since Jutland and that he was different.

No doubt the terror of battle and the loss of his brother weighed heavily on him. Tragically, Arthur committed suicide on 30 December 1919.

Walter Yeo

Petty Officer, HMS Warspite

Walter Yeo was born in 1890 in Plymouth to a naval family. His father was killed in November 1890 after HMS Serpent ran aground on Cape Vilan and sank and his mother worked at the royal victualling yard in Plymouth. Yeo joined the navy at the age of 15, and after several years of service and training, became a petty officer on board HMS Warspite in 1915.

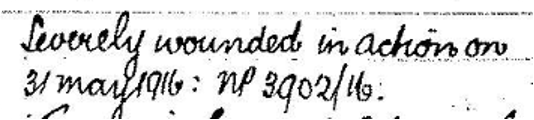

Known as the ‘Grand Old Lady’, HMS Warspite served in Britain’s Royal Navy during both World Wars. Warspite formed part of the 5th Battle Squadron at Jutland, a unit of fast battleships. She was hit multiple times throughout the battle. Yeo managed the gun in No. 6 casemate, where he received life changing facial injuries.

The HMS Warspite and HMS Malaya during the battle.

Midshipman John Bostock described the moment a cordite fire broke out in No. 6 casemate:

"We knew that the gun crew must be burnt pretty badly and this did not altogether make it a pleasant job spraying cold salt water into the casemate...I saw one dilapidated looking figure stagger froward and lean against the breakwater. I found it was the gun layer Petty Officer Yeo. He was quite calm and told me he was burnt all over and could not touch anything with his hands."

Remarkably, Warspite was able to return to Rosyth in one piece and Yeo was transferred to a hospital on land. Given the nature of his burns and the pioneering new work being undertaken by Harold Gillies at Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup, Yeo was granted a place there in August 1917.

Yeo's service record, which you can explore for yourself here.

Yeo became one of the first people to be treated with Gillies’s new technique of skin transplantation. He took skin from Yeo’s chest and created a mask that went over his eyes. After several surgeries and months spent with Gillies, Yeo was discharged. He lived until the age of 70, dying in 1960.

Trace Battle of Jutland ancestors within Findmypast's naval collection

Royal Navy stories are now at your fingertips with a brand-new, exclusive and growing archive of records charting from Trafalgar to the Second World War.

Trace ships and their crews lost to the deep in casualty logs. Track submariners as they slip beneath the surface on covert missions. Meet the pioneering women of the WRNS who shouldered vital wartime duties.

Whether you're mapping the story of a ship, a hero, or a family legacy forged in saltwater, this first instalment of Findmypast's collection is waiting for you to explore, brought online in partnership with the National Museum of the Royal Navy. Delve deeper into these never-before-seen records today.