How the 1921 Census helps reveal the rich history of Britain’s deaf community

8-9 minute read

By Guest Author | October 11, 2022

What do census records tell us about deaf history? Stephen Rigden shines a light on untold stories from the deaf community and explains how you can too.

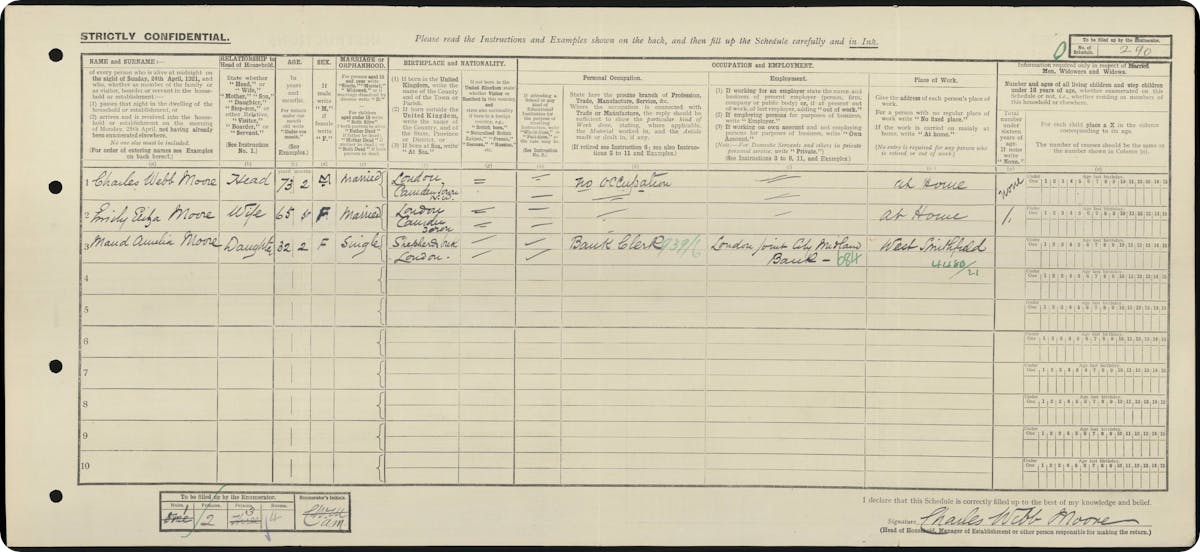

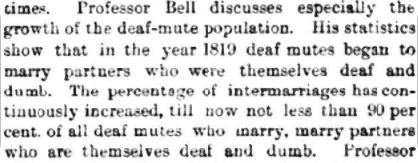

The first census of England & Wales to ask about disability was in 1851. It enquired specifically “whether blind or deaf-and-dumb”. The 1861 Census posed the same question. From the 1871 Census, the authorities also enquired whether an individual was “imbecile or idiot” or “lunatic”. The wording of the census returns then remained the same until 1901, when “idiot” was replaced by what was regarded as the more gentle-sounding “feeble-minded”. In 1911 the Infirmity column wording was modified slightly to ask whether a person was “totally deaf” or “deaf and dumb”. Seven consecutive censuses, therefore, posed questions on infirmity. The 1921 Census schedule, however, did not; it is silent on the subject. If the 1921 Census records information about disability, then it is in such fields as Occupation, in which householders have volunteered this information about family members.

There are many points of interest raised by this quick overview. Why, in the first place, was a question about disability raised in 1851? Why was blindness and deafness its primary focus? Why was the whole subject dropped in 1921?

The history of deaf and blind people in UK censuses

The fact that blindness and deafness were of greatest concern to the Census Office is confirmed by follow-up sample surveys being conducted after the 1861 and 1881 Censuses, asking further questions in respect of those who had been recorded as blind or deaf. The surveys do not survive, but received comment in the Census Office’s reports for those years.

A newspaper clipping from the Preston Herald in 1889.

It is clear that the official view was that persons such as the blind and the deaf could become a burden upon the state if they were not educated and trained up for a livelihood. While, therefore, there were genuine paternalistic and humanitarian concerns, and a wish that the blind and deaf should avoid falling into poverty, there was also a frank acknowledgement that, through proper schooling and training, the public purse would not be unduly called upon. It seems clear also that the blind and deaf were first to receive this attention because they were regarded as being educable, whereas those with learning difficulties or mental health problems would be a much more challenging proposition.

Recording the deaf in the census

Looking specifically at the subject of deafness, it is clear that there were deficiencies in returns, and the Census Office was well aware of under-recording and inaccuracy. For example, parents may not yet have been aware of deafness in a small child. At the opposite end of the age spectrum, there was the matter of those hard of hearing in old age, who often, quite understandably, appear as “deaf” in the census returns but probably were, for the most part, of little or no interest to the Census Office. What it was interested in was congenital deafness (those deaf from birth) and early childhood deafness, usually acquired through disease (such as small pox and meningitis) rather than accident. It wanted to quantify deafness so that policy-makers could review the situation and decide what measures, if any, needed to be taken by the state to supplement those already in place thanks to the charity sector.

In the 19th century, there were already a number of charitable institutions caring for, educating and training the deaf. A boarding institutional education was most likely for a deaf child, for the simple reason that in very few towns and cities would there be a sufficient number to fill a class or warrant appropriately qualified teaching staff. Private and home education was an alternative, but the specialist schooling required tended to mean that, once institutional establishments appeared, a child would attend them(and, incidentally, Guardians of the Poor were empowered to send deaf children to such specialist schools).

Institutions had all sorts of advantages beyond the educational, not least a sense of community and the opportunity to make lifelong friends and, of course, where co-educational, fall in love with future spouses. This latter in itself became a cause of some concern. A deaf couple whose deafness was hereditary would very probably, by reason of genetic inheritance, have at least some deaf children, thereby, as the authorities saw it, perpetuating the very problem they were trying to address. In this context, some wondered whether intermarriage should be discouraged.

It should be stressed that, from a deaf history perspective, intermarriage is valued. There is now a long tradition of intermarriage within the community and, indeed, of children and grandchildren attending the same specialist institutions as their parents. This is also one of the factors that makes deaf family history so interesting and a source of pride.

The deaf in the 1921 Census

So why was the infirmity question, as it was called, dropped from the 1921 Census? The simple answer is that the preoccupations of the Census Office and the government departments and others who lobbied it had moved on over the decades. There were, it seemed, much more pressing concerns as the welfare state started to develop in post-War Britain–unemployment following the 1911 National Insurance Act, the number of minor dependents, even the distances travelled to work in an age of commuting (was the public transport network fit for purpose?). And, furthermore, it was probably felt that the existing establishments caring for the deaf, for instance, were, in fact, sufficient and doing their job. Controversies around methods of teaching – signing versus oralism – were beyond its ambit.

A census page from 1911, with the infirmity question on the right hand side.

So how can those interested in deaf history make the most of the 1921 Census? It is of course, as it always is, possible to search by name for any person of interest in the usual way.

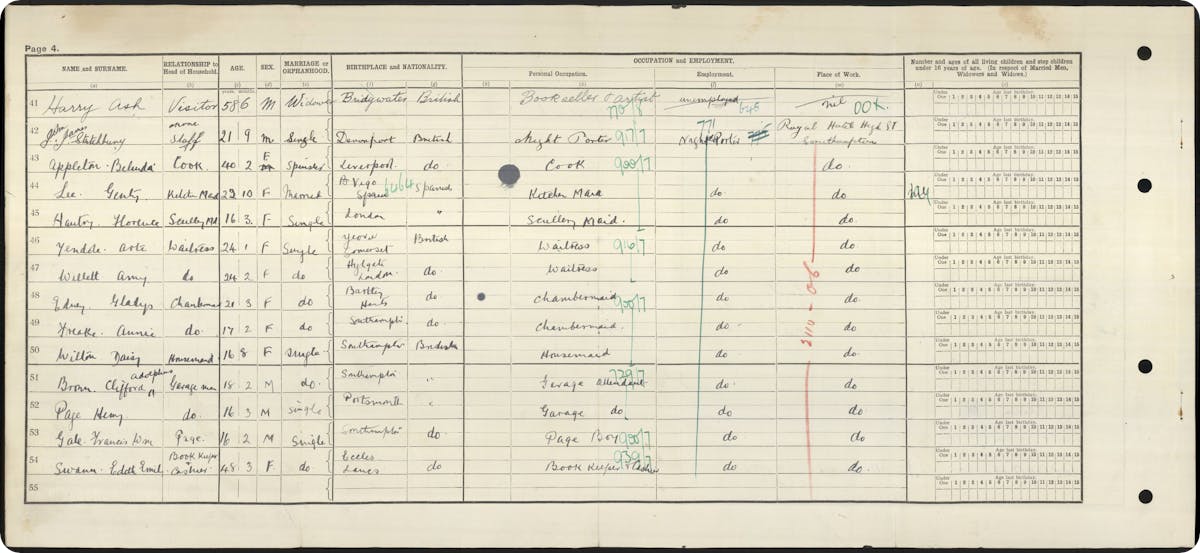

Harry Ash (1863-1934)

For example, we can look for Harry Ash, arguably the key figure in the development of modern British Sign Language. It’s easy enough to search for him by name, adding his birth year – the first entry we see is Harry Ash, born 1863 in Bridgwater, Somerset.

In 1921, he is shown as an unemployed bookseller and artist, and described as a visitor (rather than boarder) at an Ex-Servicemen’s Hostel at 64 Above Bar Street in Southampton.

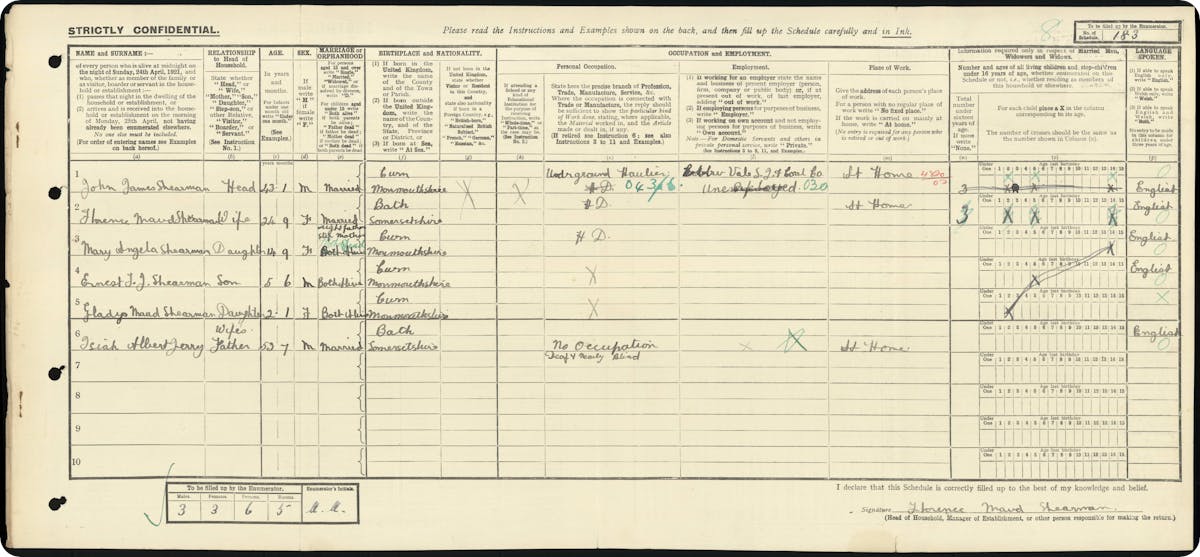

Charles Webb Moore (1848-1933)

One of the occupations for which the deaf were trained in some institutions was draughtsmanship and illustration, and there have been many deaf artists. One such is Charles Webb Moore. Like Harry Ash, he was educated at the London Asylum at its premises in the Old Kent Road.

He would appear to be the only person of that name in the 1921 Census, so is easy to find. He is described as being of “no occupation” (he was aged 72 by this time) and living with his wife Emily Eliza Moore (née Kamerick) at home in Balmoral Road, London NW2.

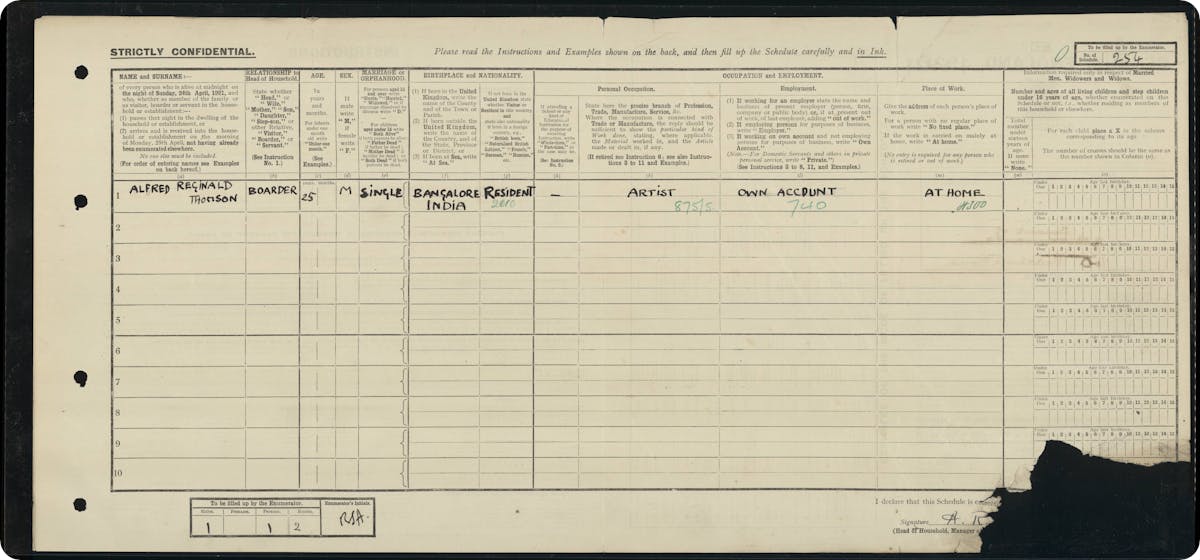

Alfred Reginald Thomson (1894-1979)

A rather different artist, of younger generation, is Alfred Reginald Thomson. He was born in India, and attended the Royal School for Deaf Children at Margate, the successor to the Old Kent Road Asylum.

Again, he is easily found on the 1921 Census, despite his common surname. He is described as being an artist and, rather curiously, as being the tenant of 40 Redcliffe Road in Chelsea, London SW10. The 1921 Census, like all censuses before it, is unconcerned as to whether the occupier of a property is owner or tenant. Indeed, by his own description, Thomson was merely a boarder. His landlady appears in the preceding census schedule, a Mrs. Edith Ross-Johnson.

Note that there is no indication whatsoever in the 1921 Census that any of these individuals were deaf. If we look for the same persons in the 1911 Census, however, we find that Harry Ash was “deaf and dumb”; Charles Webb Moore was “totally deaf from birth”(as was his wife); and Alfred Reginald Thomson was likewise “totally deaf from birth”.

Deaf organisations in the 1921 Census

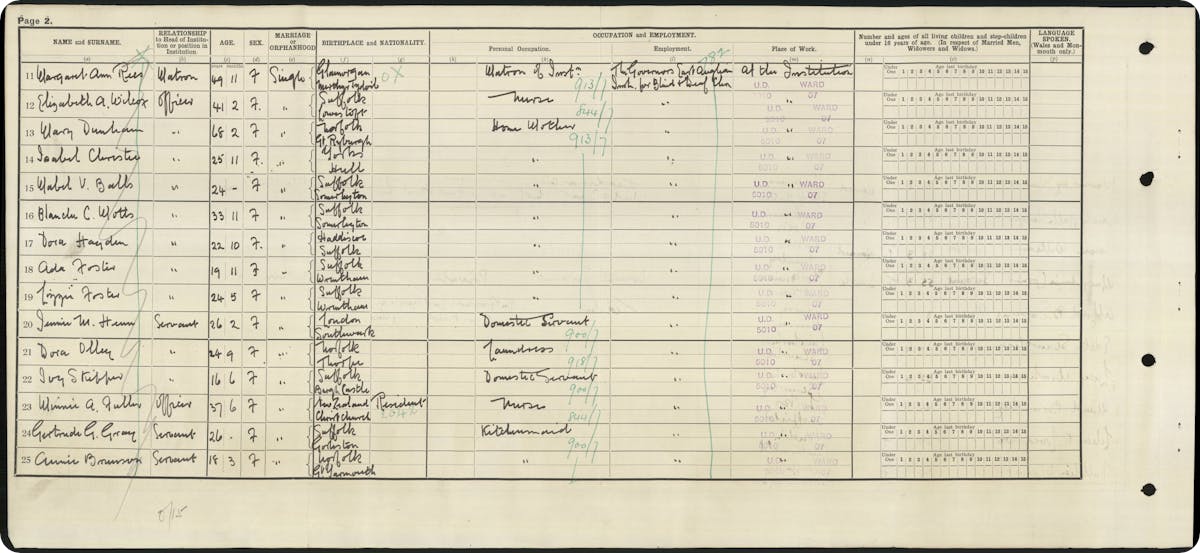

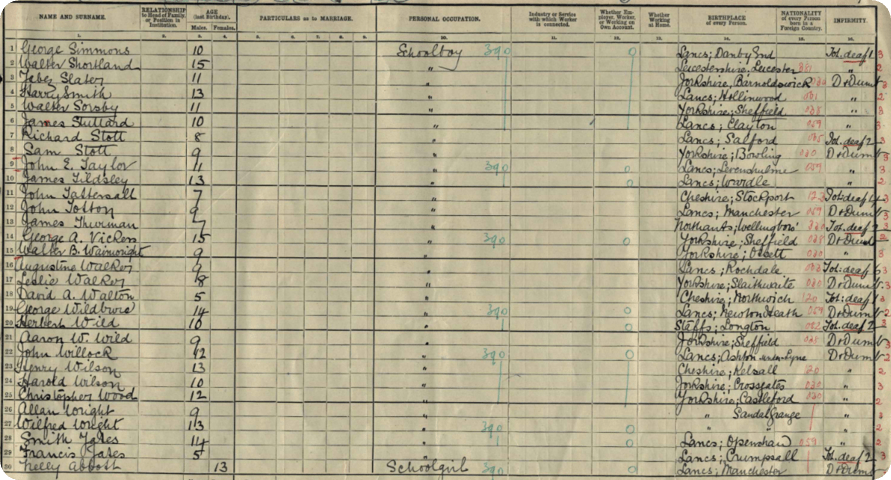

A different approach is to look for specific institutions in 1921. The largest of these across England & Wales form their own Enumeration Districts (EDs).

Deaf institutions in the 1921 Census

View full mapWe have extracted some of these in an Institutions table which you can find via a link in the Useful Links panel on the 1921 Census advanced search screen.

How to find the Institutions page in Useful Links.

It should be possible, using this table and going to the deaf history section, to search for one of the noted institutions in two ways. Firstly, you can use the advanced person search and simply search by Piece Number and ED Number. This should return all search results for the institution in question.

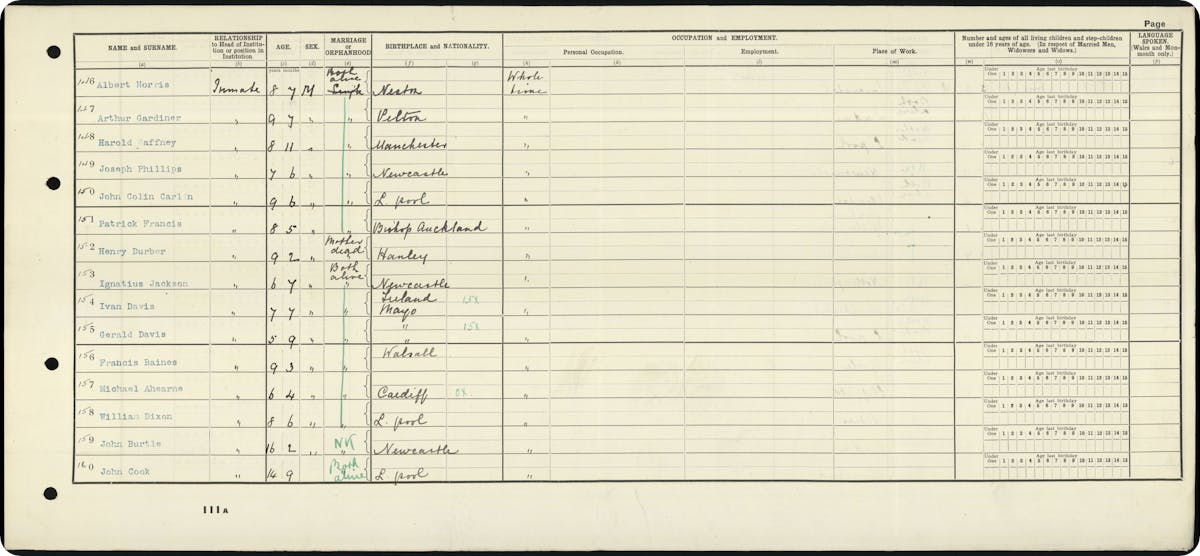

St John’s Institution, Clifford

For example, we see from the table that St John’s Institution in Clifford is in Piece 21117 (which is one of those for Wetherby Registration District) and is ED 29. Searching just using these two reference numbers gives us 267 search results. Selecting the first such result, for a Michael Ahearne, we find that he is a 6-year-old from Cardiff, whose parents are both alive, and that he is resident, as we expected, at the institution.

This was more formally known as St John's Catholic School for the Deaf, so we can infer that Michael’s family would have been Roman Catholic.

Alternatively, you can go to the 1921 Census browse experience and select the Piece Number. Note that a Piece comprising institutions will usually contain two, three or more such establishments. This means you will need to use your judgement to navigate through the images for the Piece to the right section.

Another approach is to use the Optional Keywords search box. This interrogates all fields within the underlying database in which the text is not purely numerical.

How to search via Optional Keywords.

If the word “deaf” is in the institution or address field or has been used in the occupation field by a householder to explain why a person has no employment, those records would appear in your search results. Then you can look at the transcription or the original image to find out exactly where the term is present.

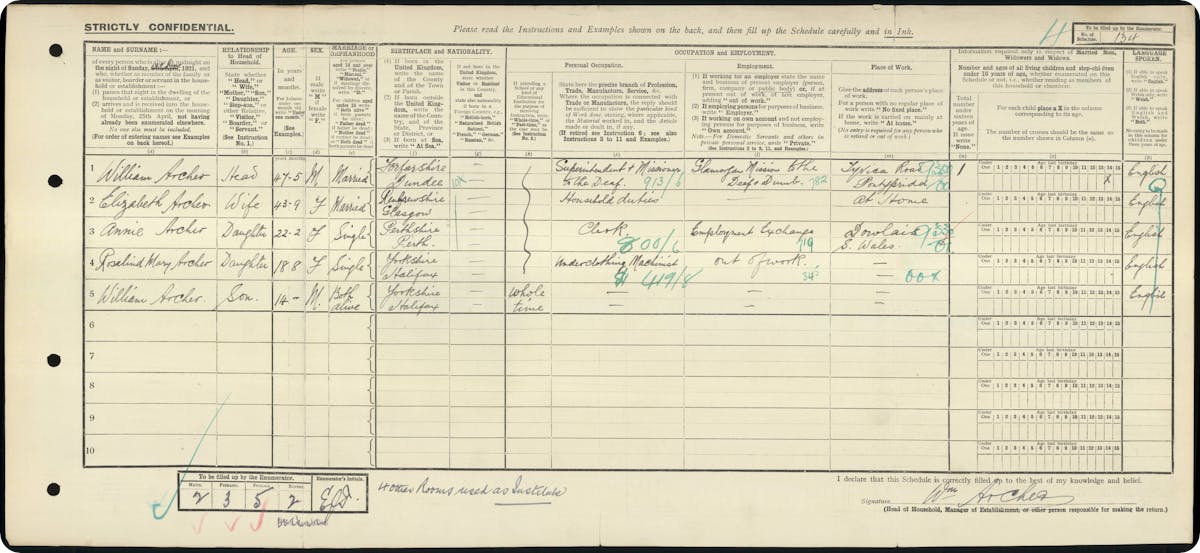

William Archer

Searching by keyword, we come across one William Archer, a Scotsman self-described as a Superintendent & Missioner to the Deaf, working for the Glamorgan Mission to the Deaf & Dumb in Pontypridd. His address is given as the Institute for the Deaf in Tyfica Road.

However, the schedule type is W, which is the standard English-language census form for Wales, and only Archer and his family are present – clearly, this was not a residential institution.

Incidentally, if we look for Archer in the 1911 Census, we find him working as a tailor in Halifax, Yorkshire and described as “deaf and dumb from birth”.

The 1921 Census reveals a wealth of information not just about your family but about communities and institutions across England and Wales a century ago. Delve into it today to see what you can unlock about the deaf community from the time.