10 Google search techniques for family history research

6-7 minute read

By Guest Author | February 23, 2021

For family history enthusiasts throughout the world, searching online is a hobby, passion, and addiction. Author of googleyourfamilytree.com, Daniel M. Lynch shares essential tips for leveraging the internet's most powerful tool for genealogy.

Building your family tree, you can spend years searching for details to complete a single box on a pedigree chart, only to be rewarded with two new empty boxes that remind you how much more you have to learn – and the call to learn, for many, is irresistible.

Search family records now

Enter a few details to see your relatives' records at your fingertips.

With billion of pages included in Google’s index of the web, however, even these powerful free tools can challenge us as we're met with a haystack of results instead of just a few precise needles.

The services provided by Google have become an indispensable assortment of tools helping us filter and find web pages, photographs, historical books and newspapers, patent filings, legal opinions, detailed maps, videos, satellite imagery, and even the ability to take a virtual walk down the streets where our ancestors walked years before.

By taking the time to understand and use some essential Google filtering techniques, you can reduce the number of results obtained for your queries, while simultaneously increasing their relevancy for your particular area of interest.

1. "WWW" may not mean what you think

When presenting at genealogy conferences, I often ask if anyone knows what the acronym 'WWW' stands for. As if reading from cue cards, the audience typically responds in unison;

""World Wide Web." "

As I remind them that we are family historians first, technology users second, their look of surprise is quickly followed by laughter.

As family historians, we are always asking Who, Where, and When.

- Who from the family tree am I looking for at the moment?

- Where were they when a particular event occurred?

- When was it that the event likely took place?

That’s the foundation for everything we do in genealogy.

Lucky for us, Google is perfectly suited to answering family history questions, as well as many others. We can greatly increase our odds of finding meaningful answers when we know how to ask.

When using Google to search the internet for clues about the lives of your ancestors, keep in mind that the keywords best suited to help you find what you're looking for lie in answering the questions who, where, and when. Often in that particular order.

2. Be specific in your search

Even when you cannot locate clues about your own ancestors, you can improve your understanding of your family story by looking at more general information for a group of people from the same time and place.

If you know your family came to the United States from southern Italy in 1902, then search for information about that group and that time frame.

For circumstances when you may not have a full name or may be unsure of a spelling, providing the elements that you do know can help Google start you down the right path.

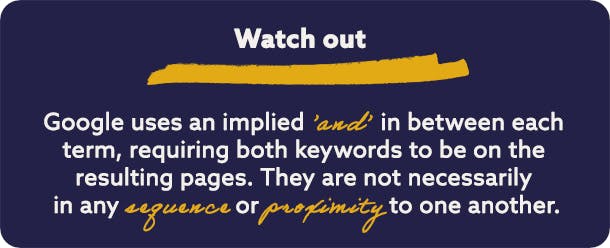

3. Understand how Google search works

It’s important to have a good foundation of the basics of what Google is doing each time you submit a search. The fact that the web is also changing every second makes it that much more difficult for many of us to fully appreciate.

Google and other search engines use automated programs, often referred to as spiders, to crawl the web in search of web pages and their links to other pages or sites. With each visit, Google catalogs the spiders' discoveries, which are then added to one of the largest and most comprehensive indexes of the web known to exist.

When we search, we are actually asking Google to look through their index of the web for matching terms, not the live internet itself. Google continually refines this process, and as a result, most queries are resolved in well under one second. Google uses as much information as it can to help ensure your results are the most relevant ones possible, while still doing so as quickly as possible

For example, Google can often detect the geographic location where your computer or mobile device is connecting to the internet, and this is useful data if your query is;

""take out restaurant""

or

""electrician""

or

""catholic cemetery""

In each example, Google can provide far more relevant results using your location and the keywords you provided, in combination with other relevant data.

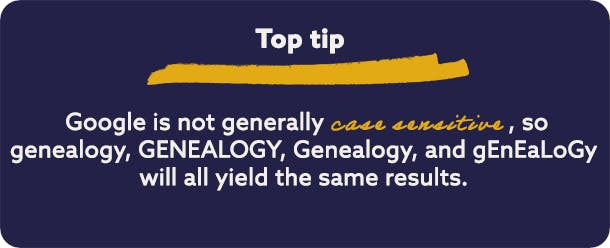

4. Use (or don't use) stop words

Another item to note is that Google will often ignore small, commonly occurring words, such as 'the' 'at' 'of.' Google refers to these as stop words and also provides a mechanism for you to use them if and when you want, if that is indeed what you want.

Consider the following examples:

- the statue of liberty returns 25.7 million Google results

- statue liberty returns 25.8 million Google results

- "the statue of liberty" returns 6.9 million Google results

A search for the statue of liberty would be processed as statue liberty. Removing ‘the’ and ‘of’ enables Google to more quickly respond to a two-word query, but also will not likely impact the relevance of the results provided.

5. Three is the magic number

According to Google, a typical query consists of three individual keywords. Using the WWW rule, you should try to provide a given name, surname, and place name for most family history queries, but only if that information is known.

Depending on who you are looking for and the dynamics of the surname, you may need to give Google more or less information. You might bed faced with too many results (in the millions) or too few results (zero).

6. Be aware of common surnames

While the surname Lynch might not be as common as Smith or Jones, it's certainly not unique.

The more common the name - especially if the word itself has other meanings (e.g. Brown, Ford, Baker, etc.) - the more important it is that you help give some keywords for context so Google can find results that have some relevancy to what you're searching for.

For example, I provide the first and last name for my grandfather, followed by the name of the city where he lived his entire life. Earlier that query had generated nearly 2.5 million results, but when I include the keyword instruction asking Google to search for only genealogy pages, the number of results drops to just 117,000.

7. Broaden your search

Placing a tilde character (~) immediately in front of the keyword genealogy is asking Google to find pages with the word genealogy or words that have a similar meaning. The resulting pages, therefore, may have the word genealogy, family tree, roots, ancestry, heritage, vital records, or a host of other words.

While searchable terms are not always pure synonyms, they are certainly words we often associate with genealogy and which Google has learned to also consider as similar words.

8. Structure your query correctly

There is no single best way to structure a search query, but through trial and error over several years, I've developed techniques that help to quickly filter results so we're left with just the type of web pages that family historians expect.

For example, if the name Patrick Lynch appears inside quotation marks as "Patrick Lynch", this instructs Google to find pages where Patrick Lynch appears as a consecutive string of characters (what Google calls an 'exact phrase match').

Next, if I add the keyword Vermont as a location name, but I place a minus symbol (-) immediately before it, this instructs Google to exclude all pages that contain the word Vermont.

This filters out the pages dealing with Patrick Lynch from Waterbury, Vermont. My family lived in Connecticut. This has reduced the number of results from about 117,000 to fewer than 1,000.

These examples show how you can use a few additional filters to remove a significant number of results that are not likely to have any relevance for your own family research.

9. Take spelling variations into account

Name variations are another common challenge faced by many family historians. It is not unusual to find two or more variant spellings for the family surname.

In my case, my paternal grandmother had the surname Phelan. Or was it Phalen or Phallon or Whelan or Whalen? I've seen it so many different ways on official documents; it's hard to know for sure. Your family name may have been changed altogether for a variety of reasons.

In this case, I can use the 'OR' operator between two common variations of the surname Phelan. This is placed between one or more terms and must appear in UPPER CASE for Google to perform the conditional search, allowing either result to appear in your results. Undercase ‘or’ will be ignored as a stop word.

I used the two most common spellings for my grandmother's maiden name, along with other keywords described earlier. With just 534 results, it's likely that I could quickly find something of relevance.

This same technique can be employed when you are not certain about a location. If family legend has it that your great grandparents came to America through the Port of Boston, but you have a clue that points to Philadelphia, then search for 'boston OR philadelphia'.

10. Practice makes perfect

Hiding somewhere in that worldwide haystack are clues that may be of interest to you and a few others researching the same family. Often, the accidental discoveries are the ones that provide the most fascinating clues.

Experiment using your keywords, quotation marks, the 'OR' operator, the minus and tilde symbols to further refine your query. While they can be used in any order, I'd suggest trying them in the order listed within the examples shown for the best results.

Please also remember that not every query needs special characters – you should filter gradually, refining your query based on the number of results you obtain. This will help prevent you filtering past something that may be highly relevant.

Additional techniques are described in my book, Google Your Family Tree and you can find free details for other more advanced family history queries at GoogleYourFamilyTree.com.