Were your ancestors caught up in the Irish War of Independence?

3-4 minute read

By Brian Donovan | November 7, 2022

Discover the remarkable stories of the rebels who fought against British rule in Ireland with Brian Donovan's expert family research tips.

The Irish War of Independence raged from January 1919 until July 1921. It pitted the Irish Republican Army (IRA) against British soldiers and ultimately ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the formation of the Irish Free State.

Some of the most famous names in Irish history were at the forefront of the struggle for independence - Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, and Eamon De Valera. But everyday people also became embroiled in the conflict.

Was your family involved? What was life like for them? If you have ancestors who were in Ireland at the time, you’ve probably asked yourselves those questions. Maybe you’re anxious to finally prove a treasured family tale or fearful for what you might find if it is true. The excitement and drama of rebellion can be captivating.

But it was a violent conflict after all and there is nothing pretty about that. Death, broken lives, terror, and trauma are the stuff of war and revolution. So, if your family endured this period in Irish history, how do you unlock their stories?

Here’s a quick overview of the records you can explore. It’s not exhaustive, but will guide you through the main avenues for research online at Findmypast and elsewhere.

Rebellion records

We are exceptionally lucky that so many records survive from the 1916 Easter Rising and the War of Independence from both sides. One of the best sources to start with is the Sinn Féin Rebellion Handbook, a special edition issued by the staunchly unionist Irish Times in 1917 documenting the events of the previous year. While it was not sympathetic at all, it is packed with names of rebels, soldiers, police, civilians, casualties, and more.

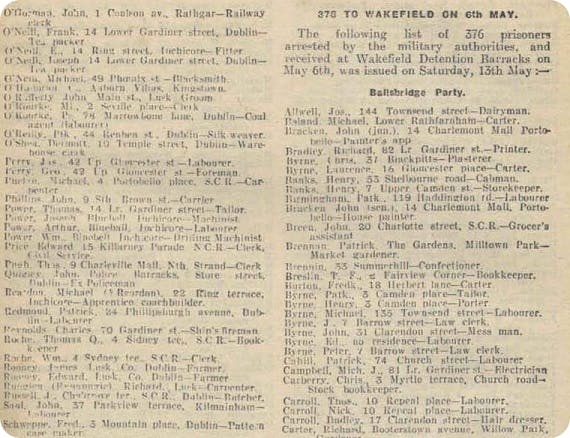

Lists of prisoners that were deported and released, including their names, addresses, and occupations. View the full record.

The Military Archives in Dublin has published an extensive collection of interviews, images, and audio files with participants of the 1916 rebellion and the War of Independence compiled by the Bureau of Military History in the 1940s. Many of those who were active in those struggles were veterans of World War 1, radicalized like so many others across Europe by the horrors they witnessed.

The Military Archives are also publishing the pension and medal files for those who were active during the revolutionary period. So far, around 33,000 files have been published online. But there are over 300,000 pension and medal applications, with over 80,000 claims of military service, so the archive in Dublin is worth a visit too. They continue to digitize the extraordinary archive of rebel military leader General Michael Collins too so you can see how he managed the clandestine IRA men and directed the war.

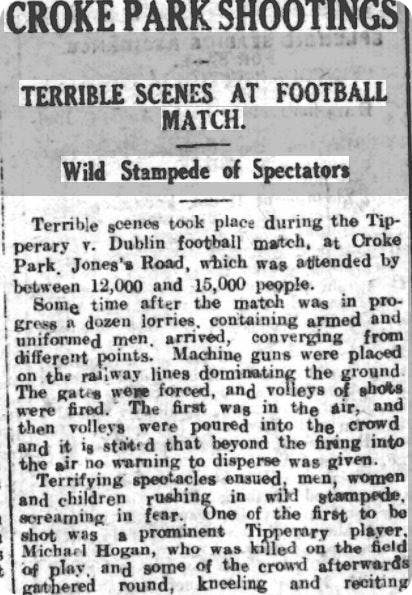

Bloody Sunday on November 21, 1920, was one of the worst atrocities of the Irish War of Independence. Read about it in our newspaper archives.

You can also find records of those who served in the Free State army in their 1922 Army census, available on Findmypast.

Ireland under martial law

In 1916 and 1919-21 Ireland was placed under martial law. This meant that the British administration at Dublin Castle took charge of all civilian matters. They were given extraordinary powers to search, arrest, detain and pass judgment, up to and including execution. Fortunately (for family historians), this also required meticulous record-keeping and thousands of original documents from the time are now searchable online at Findmypast.

Easter Rising

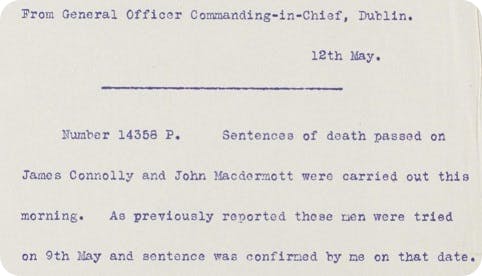

The army files for 1916 are very informative about the suppression of the Easter Rising. They include daily situation reports from April 24 until the last execution (James Connolly) on May 12, details about the prosecution of those detained, and investigations of individual deaths.

All of these files contain copious information on rebels, soldiers, police and civilians caught up in the event.

Raid and search reports

Martial law didn't come to an end until the truce on 11 July 1921. The vast majority of the army files relate to the post-1916 period and are very extensive. They also document in detail those who were caught up in events without any active involvement. In fact, the heavy-handed response of the British military, and the ‘Black and Tans’ drove much of the population into the arms of the rebels.

The records include raid and search reports. Under martial law, the army had the power to search and detain without a warrant. As a consequence, they carried out over 20,000 raids of premises all over Ireland, often in the middle of the night.

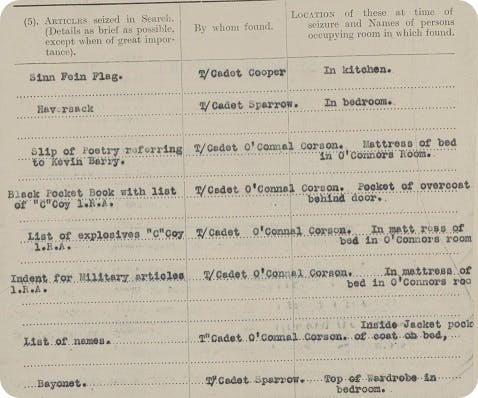

An example of a raid and search report listing seized items. View the full record.

Every raid required a report to be filed by the military squad involved. These are very informative including details of the occupants of the premises, the squad of soldiers, what was said, and what was found.

Prison registers

When someone was arrested under martial law, they could be detained indefinitely under the Defence of the Realm Act. You’ll find their prison records online at Findmypast.

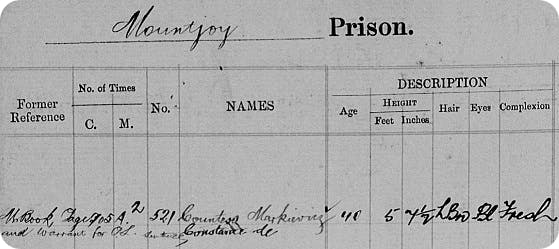

Constance Markievicz’s detailed prison register from 1920. View the full record.

A continuous source of shock to the British authorities was the number of Irish women involved in the rebellion. There are extensively detailed files concerning what to do with them.

Court martials

While internment was commonplace, many of those arrested were brought to trial before an army officer in the local barracks and these courts-martial trial registers and files survive too.

For example, on 1 November 1920, John Corcoran of Castlecomer in County Kilkenny was caught up in an incident:

"“Military went to Courthouse Castlecomer to post up notices, some 20 civilians were near it. They were ordered 'Hands up' all complied except accused who rushed at one of the party in a ferocious manner, saying 'I defy the military', he was wounded by a shot.”"

John was handed 14 days' hard labor for his trouble.

While few fought in the Anglo Irish War, it impacted the lives of ordinary people in many ways. They had to endure random arrests, midnight raids, intimidation, and more. It also happened in parallel with the First World War which left deep scars throughout the country. It was a traumatic time, but today, we are fortunate to have records to make sense of it.