The Black Loyalists and the importance of preserving Black history records

6-7 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | February 19, 2021

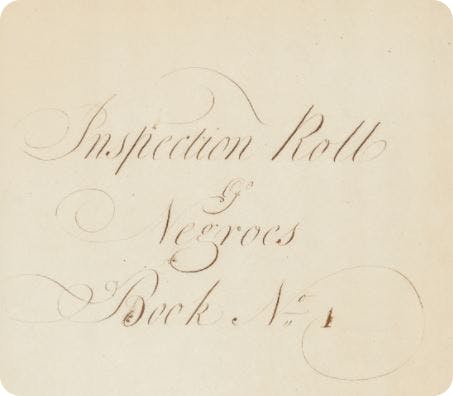

Transcribing the 1700’s Inspection Roll of Negroes, Findmypast’s Stephen Rigden discovers the Black Loyalists, a little-known part of the American Revolution.

Please note that the terms used in historical records reflect the attitudes and language of the time and may now be considered inappropriate, derogatory, or offensive.

Most family records are only accessible online because they have been transcribed or indexed. In a painstaking process, handwritten historical records are licensed, conserved, and digitized before being transcribed and made searchable online.

Explore family records now

Enter a few details to discover your past.

Most of us take the transcription process for granted. We enter our search criteria, click on the search button and expect to see the results of interest to us. But your family history is at your fingertips because the original handwritten or printed records have been transcribed by somebody else.

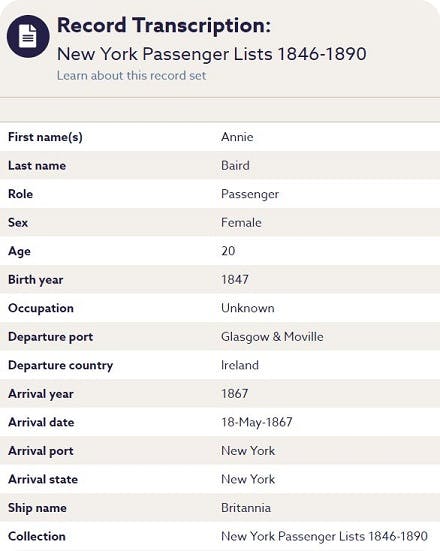

Important family information is captured on Findmypast's transcripts, like this one taken from a passenger list. View the full record.

At Findmypast, we do many of our own transcriptions. Others have been contributed by our partners, such as the many excellent local family history societies gathered under the umbrella of the Family History Federation.

It’s only when you transcribe records yourself that you truly appreciate what’s involved. When you have an original handwritten historical document in front of you and have to read every single word and look at every letter carefully, you really begin to understand it. It’s a slow process that sees you engage with the document itself and the lives and times of the people recorded on the page.

Transcribing Inspection Roll of Negroes, 1774-1789

Recently, I transcribed the records of Black Loyalists evacuated from New York by the British in 1783 following defeat in the American War of Independence. There are two different copies of the original document that were created at the same time. One copy was created by the defeated British and has been deposited in The National Archives in London. It’s in a single-bound volume and its title is simply Book of Negroes.

The second copy was created by the victorious Americans and has been deposited at The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington DC. The title of this second copy is the Inspection Roll of Negroes. There are many small differences between the two versions, including paging and sequencing of records. Both contain errors.

For Findmypast’s version of these important records, I decided to use the American title as it’s more descriptive.

What is an inspection roll?

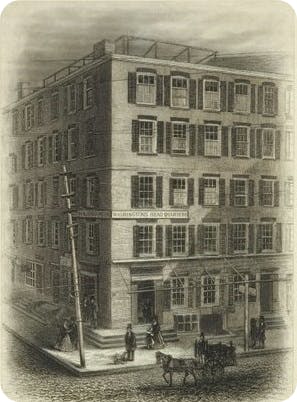

These documents were called inspection rolls because they were the records created by American inspectors of all Black persons preparing to board the British vessels at Staten Island. Although the British likewise registered the Black evacuees, they were not inspecting them as such. They had already established the bona fides of the Black Loyalists, largely via interviews held previously at New York’s Fraunces Tavern.

Fraunces Tavern, New York acted as George Washington's headquarters for some time.

The Americans inspected and registered each and every Black evacuee, including their status and former enslavers, in the expectation that they would be returned to them by the British, as part of the final treaty terms in due course. The British went along with this as a charade, having no intention of returning Black Loyalists to the Americans. They had granted freedom to them in exchange for their support and loyalty in the recent War of Independence and intended on honoring their promise.

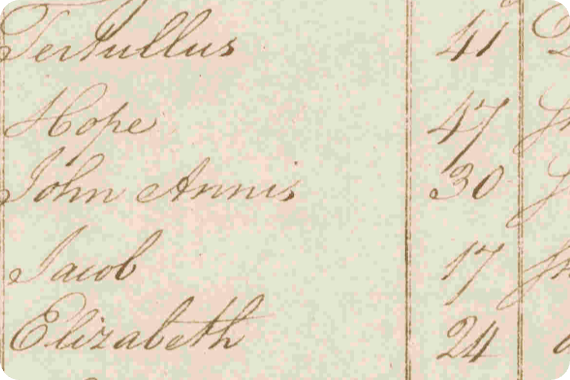

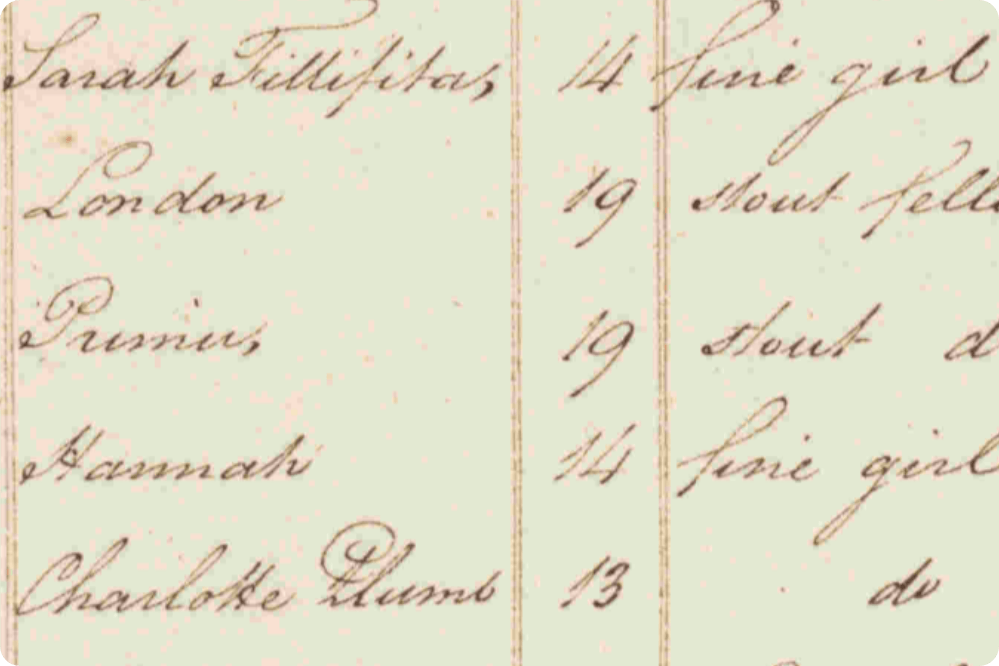

There are over 3,000 individuals included in the Inspection Roll. For each one I transcribed:

- Their name

- Their age

- A physical description

- A past history

- Details of the vessel they traveled on, its captain, and destination

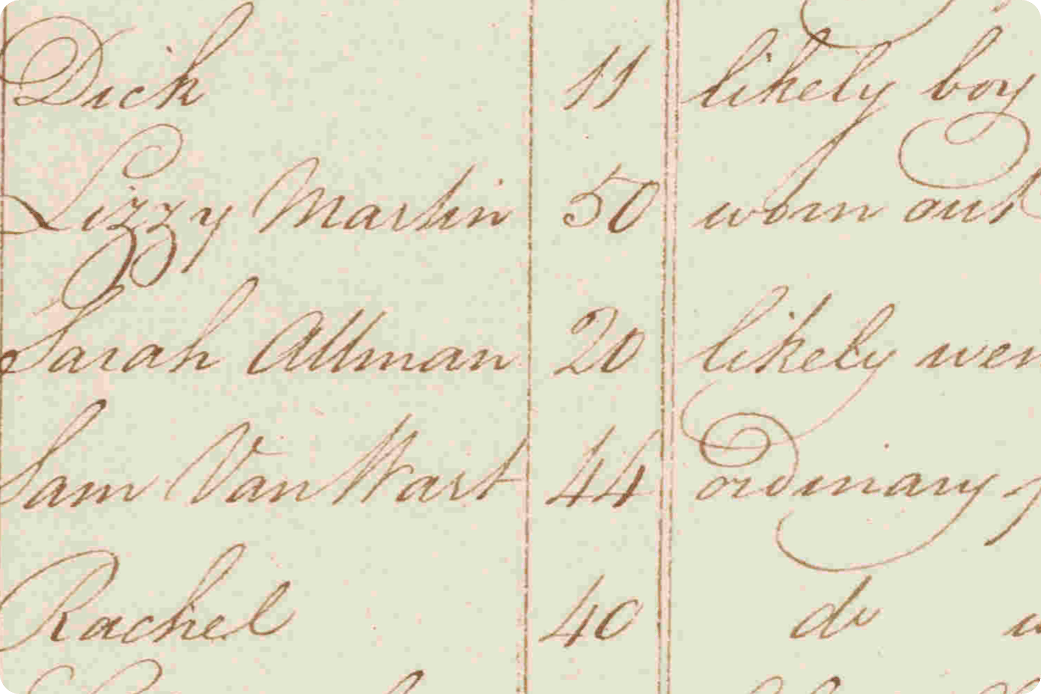

The handwriting in the documents is mostly legible. Spelling is not perfect and as a transcriber, you have to decide whether to let each irregular or non-standard spelling or apparent misspelling, stand or to silently change it. Usually, I allow the original spelling to stand, although this is not necessarily helpful to researchers, who then may not find the entry when searching.

I decided to standardize place names in order to make the records more discoverable.

Each one of those 3,000 records represents a person. A lived history mostly of enslavement, journeying into an unknown future. When transcribing, you read and repeat

"“formerly the property of” "

and

"“formerly slave to” "

hundreds and hundreds of times, and you cannot help but think about what lies beneath each record.

Thought-provoking finds

The details in the records give you a window into a world most can only imagine. Here are just a handful that struck a chord with me:

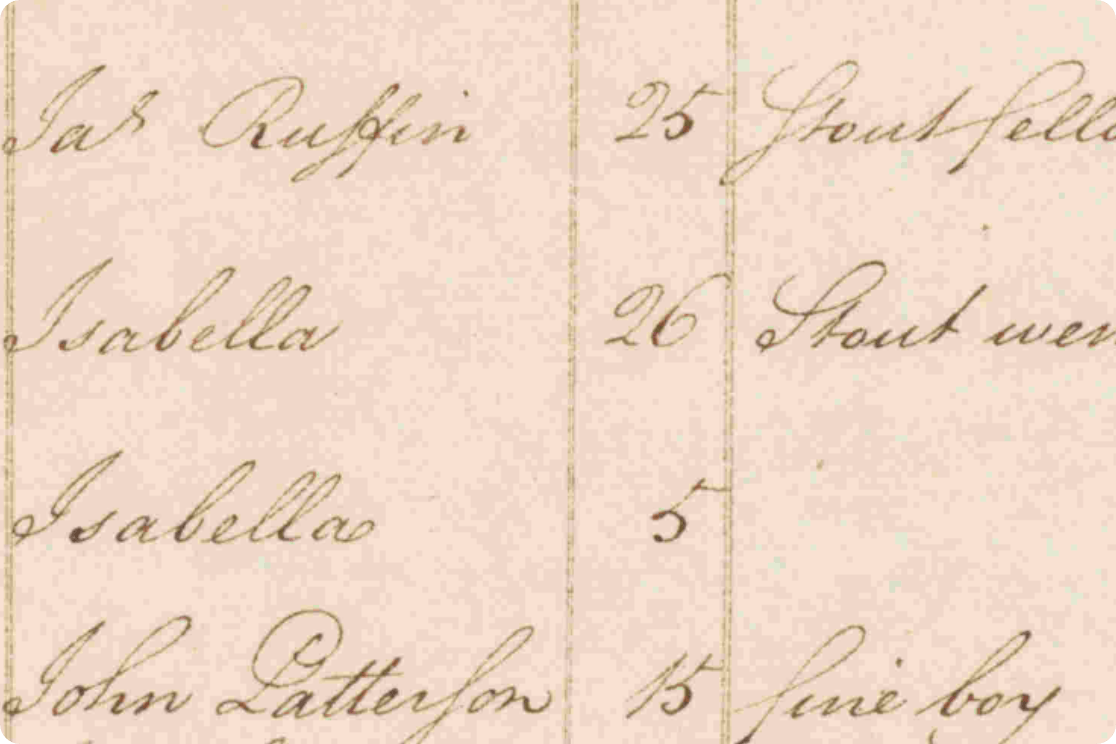

26-year-old Isabella, charmingly described as a stout wench, evacuating with her 5-year-old daughter, formerly slave to Resolved Waldron of Brooklyn, from who she ran away about 5 years ago. View her record.

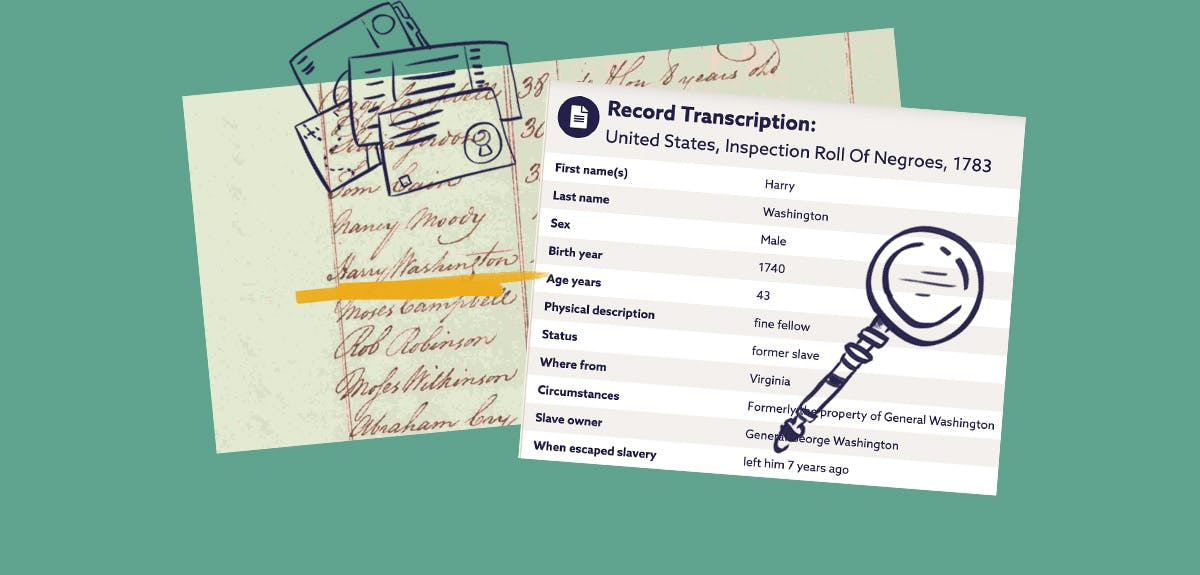

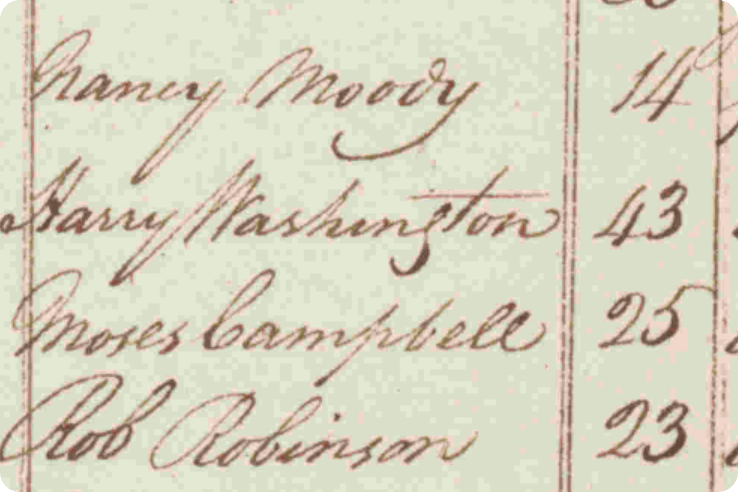

43-year-old Harry Washington, a fine fellow, formerly the property of General Washington. Yes, that General George Washington, who was soon to become the first President of the United States. View his record.

Lizzy Martin, aged 50, worn out, formerly slave to Benjamin Fowler, Horseshoe, South Carolina, who she had left early in 1780. View her record here.

These and the other 3,000 or so human beings that were leaving New York, were, for the most part, boarding ships to what we now know as the Canadian Maritimes – Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Imagine having lived as a slave in subtropical Georgia or Virginia, and to be heading into an uncertain future in the fog and the chill of Atlantic Canada. But at least they were free.

Slaves of white loyalists

Or most were free. Not all on board these ships were Black Loyalists. Around 12% were the slaves of white Loyalists including:

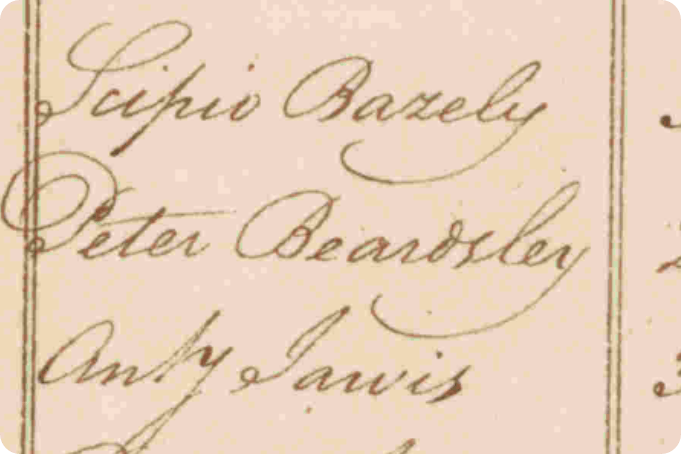

24-year-old Peter Beardsley, a stout fellow, who was the property of the Rev John Beardsley. His Loyalist master was taking him from one place of slavery to another. View his record here.

17-year-old Jacob (no surname), a stout lad, was the property of John Norris. Everyone accepted that as per the Bill of Sale produced. Here is his record.

19-year-old Primus, another stout fellow, was the property of George Thomas of the King's American Dragoons. Thomas had the receipt to prove it dated 2 December 1782. He bought Primus in Charleston SC from John Woodberry.

Slave names

Like Harry Washington and Peter Beardsley, there are many examples of slaves named after their owners in the Inspection Roll of Negroes. It is not a coincidence. It doesn’t (usually) mean that the enslaver fathered the slave. In most cases, the slave was given the surname by his enslaver. Not even their name was really their own.

As far as I know, none of the people in these records are related to me. I wouldn’t normally find them while researching my family tree. But transcribing their records has expanded my knowledge as a genealogist. Genealogy is nothing without local and social history - the bigger picture of the past.

I’d recommend occasional transcription work to all family historians as a way of enlarging and enriching your understanding, and as a way of walking in the shoes of others. Think of the perpetrators and victims you might come across in crime records. Think of the poor souls admitted to workhouses. Think of the infant deaths in burial registers and their grieving parents. And, in records like these inspection rolls, think what it would have been like to have lived your life as the property of another person, to have had no freedom and no life fully your own.

Transcription is also a way of giving back. By preserving records, you create something that you hope will be of value to others in the wider world. I hope that my efforts in transcribing the Inspection Roll of Negroes will help other researchers, whether their ancestor was named in the Inspection Roll or not.