'Their hunger will not allow them to continue': the victorious London dockers' strike of 1889

5-6 minute read

By Charlotte Ward Kelly | July 15, 2024

Delve into an important chapter in British labour history with Findmypast.

The Docklands have been at the heart of London’s maritime and commercial history for centuries. Throughout this time, they've employed hundreds of thousands of people.

In the summer of 1889, thousands of dock workers went on strike in protest over conditions and pay.

The strike was significant, not only in the history of the docklands but also in labour and union history.

The docklands: a short history

Founded by the Romans around AD 47, London grew around the River Thames, the city's lifeline. The cargo was brought into London along the Thames and traded. Ships would dock in what was known as ‘the Pool of London’, running between the City and Southwark.

This area was chaotic, cramped, and had little protection from the elements or thieves. Attempts were made to alleviate the pressure - the embankment of the Thames helped by adding useable land in Deptford, Rotherhithe and the Isle of Dogs.

Legal Quays Map, Wikipedia

In the 18th century, activity along the Thames grew rapidly due to Britain’s global expansion and trade. The legal quays created a bottleneck and it was said that you could walk across the Thames just by stepping from ship to ship.

Ships could not dock and their cargo would either spoil or be stolen. It was soon realised that, with industrialisation and further growth, the Thames and London would not be able to cope.

The issue of the London Docks was discussed in the House of Commons, 13 February 1796.

Further docks were built between 1805 and 1880. These included:

- The London Dock (1805)

- The East India Dock (1805)

- The Surrey Dock(1807)

- The Regent’s Canal Dock (1820)

- The St Katherine Dock (1828)

- The West India South Dock (1829)

- The Royal Victoria (1855)

- Millwall Dock (1868)

- Royal Albert Dock (1880)

The King George V Dock (1921) was the last of London’s upstream enclosed docks to be built. Ships would arrive along the Thames and be directed into a dock. The cargo would be checked, unloaded, and transported to warehouses, where it would be stored, displayed, and sold.

The last vessel to be loaded left on 7 December 1981. After this, the Docklands went through a major redevelopment with the opening of Canary Wharf, the DLR, City Airport, restaurants, the ExCel, hotels, and commercial buildings.

Living and working around the Docklands

The construction of the Docks brought employment to the area. Some men were employed permanently, earning 20-30 shillings a week (around £60-£90 in today's money), depending on the job and skill.

These employees were supported by casual labourers during peak season who would earn around 5d per hour - approximately £1.20. For casual labourers, work was not guaranteed.

Munitions Heroes, British Newspaper Archive.

Dock work was tough and dangerous. Men were injured by the heavy cargo, dangerous working conditions, and often picked up health conditions from inhaling things like asbestos. On 19 January 1917, TNT blew up at a munitions factory in Silvertown, killing 73.

Work was precarious - each day, thousands of desperate men crowded at the gates of the docks in the hope of a day's work. This was known as the ‘call-on’.

The Call-On, via https://islandhistory.wordpress.com/2014/01/08/the-call-on/.

A foreman would appear to select workers for the day and there would be a frenzied, often violent, push to the front to be seen.

The 1889 dock strike

By 1889, there was growing unrest amongst London's dockers. Casual labourers were fed up with the daily humiliation of the ‘call-on’ and the terrible pay that was not enough to feed them, let alone their families.

Inspired by the success of the Bryant and May match girls’ strike in 1888, the workers put demands on their employers on 12 August 1889. These included an increased rate of pay to 6d (known as the ‘docker’s tanner), fixed call-on times and better working conditions.

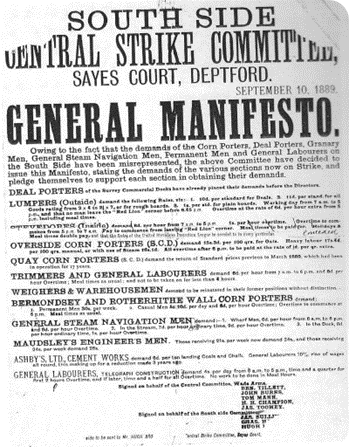

The strike's manifesto, via Wikipedia.

The men's demands were rejected, and a strike was called. Remarkably, the casual labourers were joined by their skilled colleagues including stevedores and lightermen. Soon over 75,000 men refused to work.

The strikes were organised by the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers’ Union, led by union leaders including Ben Tillett, John Burns, Tom Mann, Ben Cooper, and Will Thorne. They knew the importance of gathering public support and media interest so held rallies, processions, and mass meetings throughout London.

The strikers were met with support from locals, many of whom would have been affected by the strikes. The protests were widely reported in the press, with some criticising the actions and the power of the unions.

The men forfeited their pay to strike, and this made donations to the cause vital to pay for food relief tickets. The dock and ship companies believed that starvation and the impact on their families would soon bring an end to the strikes - but donations were received from around Britain and the Commonwealth.

The London Dock Strike, Wikimedia.

The largest donation came from the Australian labour movement, which gave a massive £30,000 to the cause. The pauses in trade to London caused by the strike had impacted their livelihoods, yet they supported the cause of their British brothers-in-arms.

A popular workers' chant from the time goes:

"Sing a song of sixpence,"

"Dockers on the strike."

"Guinea pigs are hungry,"

"As the greedy pike."

"Till the docks are opened,"

"Burns for you will speak."

"Courage lads, and you'll win,"

"Well within the week."

The strike brought London’s ports to a standstill. Ships were queuing, cargo was turning bad, and profits dramatically decreased. It put London’s global reputation at risk. This prompted the Lord Mayor to get involved and reopen negotiations between the unions and the companies.

On 15 September 1889, the strike ended and the dockers received most of their demands, including the important ‘docker’s tanner’.

Brighton Argus, 16 September 1889. View this page.

Though the strike only lasted a month, it highlighted the importance of united workforces and the power of unions.

Did a member of your family work on the historic docks? You can find your Docklands ancestors by searching our world records page and the greater London marriage index. To delve even deeper, explore records for Lightermen and Watermen here.