Irish family history and minority religions in Ireland

5-6 minute read

By Brian Donovan | July 15, 2024

Brian Donovan takes an in-depth look at Ireland's minority regions and offers his top tips for researching ancestors from the Emerald Isle.

There is a perception among many that Ireland has always been an entirely Roman Catholic country. Certainly, in 1961, 95% of the population of the Republic of Ireland stated they were Catholic. This connection had been consciously reinforced by the fledgling Irish Free State following independence in 1922.

It was underlined by the partition that divided the country in two, leaving a rump province of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, defined as much by its Protestant faith as by its loyalty to Britain.

Discover the stories of your Irish ancestors

Does your family tree have roots in Ireland?

This confessional split is probably the only aspect of Irish religious diversity acknowledged by most family historians. But genealogists, just like historians, should be wary of reading history backwards.

The myth of Ireland's religious polarity

There was nothing inevitable about the religious history of Ireland, and its 20th-century manifestation should not obscure or simplify the earlier reality. Genealogists recognise that every family is specific - they need to maintain an open mind, especially when it comes to religion.

It might come as a surprise to many that in 1841 37.5% of Ireland was not Catholic and all evidence suggests the percentage was considerably higher in earlier years. This should come as no surprise.

The Penal Laws

The Penal Laws, enacted from 1695, restricted and stopped Catholics and Protestant dissenters from the Established Church (the Episcopalian Church of Ireland) from owning land, entering professions, voting and running for office.

These regulations enabled the Church of Ireland to become the largest 'minority' faith in the country, despite its status as the 'church by law established'.

St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

While it is unlikely that more than 20% of the entire population were ever adherents, they were concentrated in the eastern half of the country - the population more likely to speak English, who also had greater access to the new opportunities afforded by the growth of the British Empire.

If your ancestor was a member of Ireland's established church, you can search for their name within our Church of Ireland Parish Registers.

Religion, empire and immigration

From 1610, the Ulster Plantation brought a large influx of Scottish Presbyterian settlers to the north of the country. This process accelerated during the following century, as the opportunities afforded by settlement in Ireland far outweighed those in the distant inhospitable American colonies.

Ulster Plantation.

This changed, and as the penal laws came into effect, this group (who we remember as the Ulster-Scots or Scots-Irish), began to migrate in significant numbers to colonies like Pennsylvania where there was no religious barrier.

There are few Presbyterian parish registers online, but this short article by Fiona Fitzsimons in History Ireland magazine provides an excellent introduction.

The role of religion in British allegiance

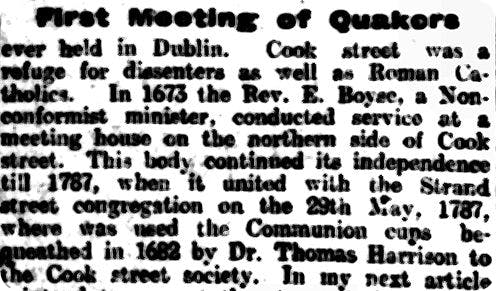

Despite the penal laws, it was still easier to be a Dissenter - be that a Baptist, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, Quaker or the many other protestant denominations - in Ireland than in Britain.

These communities were generally considered to be in support of continued British control of the country, so the penal laws were not enforced in Ireland with the same rigour as in England.

A report on religious dissenters in the Dublin Evening Telegraph, 20 August 1910.

Paradoxically, that also made Ireland an easier place to be an English Catholic, as they were also generally aligned with British authority based on their cultural affinity. Like so much else in Irish history, loyalty to the British state, just like social class, played a far more important role in defining the identity of Irish communities than religion.

This religious tolerance for minority Protestant faiths is precisely why Ireland became a popular haven for so many in the period after 1650.

This started with the English Republican Baptists and Quakers who settled in Ireland in large numbers from the mid-17th century, bringing with them their radical political ideas of individual liberty.

They remained in Ireland after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, but not for long.

Both the English Republican Baptist and Quaker communities migrated in large numbers to the American colonies. By the 19th century, their number had reduced drastically.

The British government also actively settled continental European refugees like the French Huguenots and Palatine Germans in Ireland in the late 17th and 18th centuries. This was part of the political project to increase Protestant sympathy in the country.

Father Mathew's Quay, Cork.

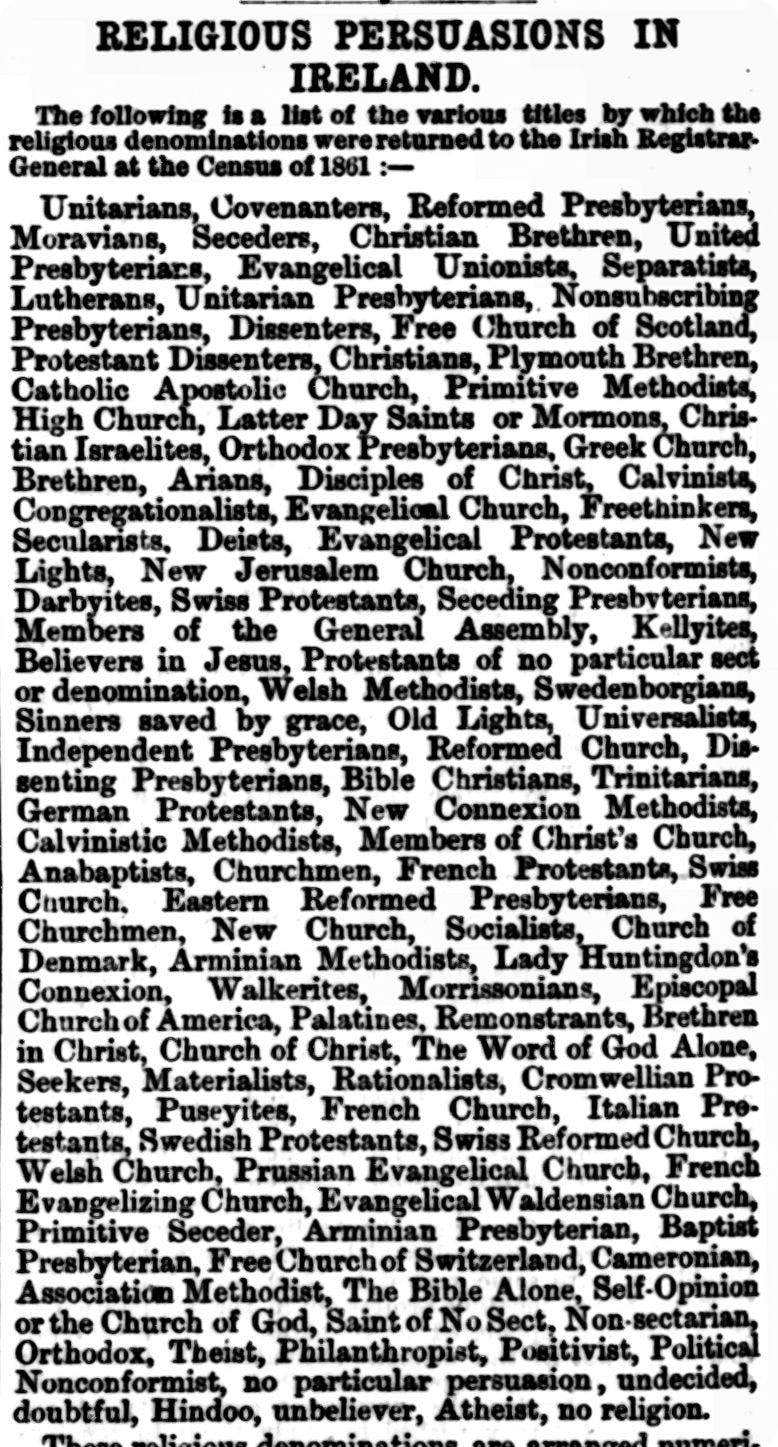

By the 19th century, and following the repeal of the penal laws, Ireland was the chosen location for the establishment of many new religious denominations like the Christian Scientists, the Church of Jesus Christ of the Later Day Saints (Mormons), and many others that have subsequently disappeared.

The 1911 Irish Census reveals the huge diversity of religious denominations - explore the many shades of Irish religion for yourself, with everyone from Cooneyites and Tramp Preachers to Waldensians to be discovered.

Irish migration to the US

Throughout this period, members of the Church of Ireland and Protestant dissenter denominations chose to migrate in growing numbers to America. In fact, before the 1840s, most Irish migrants to the United States were protestants.

As so many of them were English-speaking Episcopalians, they quickly integrated and lost their cultural identity within a generation or two, as did many Irish from the East Coast who migrated to England at the same time. As a consequence, their story has been obscured, and the community often only retains vague memories of an association with Ireland.

Irish immigration to the US, reported on in the Belfast Weekly News, 26 November 1914.

Moreover, the unprecedented scale of Catholic Irish migration from the Famine onwards created a large self-conscious community in America that came to be defined as the archetypal Irish-American. As any genealogist will know, the truth is far more complex.

Tracing Irish ancestors

What does this complex picture of migration and religion mean for tracing Irish family history?

For a start, it's necessary to remember that large parts of the country were pluralist. So, despite centuries of state-sanctioned religious discrimination and widespread sectarianism, Catholics and Protestants of every persuasion lived in proximity. Moreover, they intermarried regularly, switching faiths as they did so.

Religious denominations in the 1861 Irish Census, reported on by the Norwood News, 1868. View this page.

The religious hierarchies of every denomination disapproved and insisted that their members isolate themselves from the dangerous 'other', but human nature is its own master.

Irish culture is also surprisingly egalitarian. Irish people found ways of circumventing the rules, whether it was the penal laws or religious restrictions.

For example, it was common in 19th-century Dublin to baptise children in both the Catholic and Episcopal faiths, thereby ensuring they could marry who they wished in later life. When digging into the lives of Irish ancestors, you should expect to find more than one faith - it would be unusual if you don’t.