How Dunmore's Proclamation and the Ethiopian Regiment shaped African American history

3-4 minute read

By Jen Baldwin | July 2, 2021

In 1775, Colonial governor, Lord Dunmore made a proclamation encouraging slaves to fight in the American Revolution. At the time, he couldn’t have known the long-lasting impact it would have...

Slave revolt was one of the most feared events in the southern colonies of America. Plantation owners across the colonies realised that, as the American Patriots became more active, the possibility of runaway slaves became increasingly likely. They fought hard to prevent it, and the British were just as aware of the power of such a revolt.

When the American Revolution broke out, John Murrary, Earl of Dunmore was serving as the Royal Governor of Virginia.

During the Battle of Kemps Landing on November 5, 1775, an enslaved man, serving alongside the British regulars, came face to face with his former enslaver, Joseph Hutchings, a local militia commander. Hutchings fired at him point blank and missed. In retaliation, the black soldier wounded him with a sword.

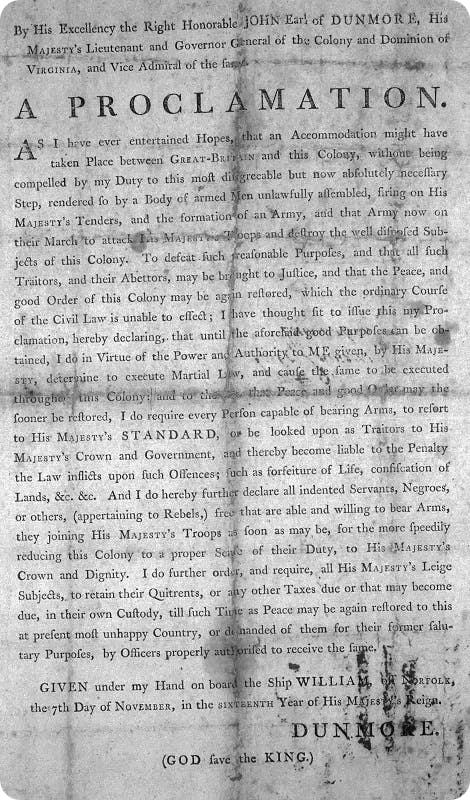

Fearing the increasing activity of the militia units nearby, Lord Dunmore issued his fateful proclamation on November 7, 1775. It offered freedom to slaves who escaped and joined his regiment to fight the rebels.

A complete transcript of the Proclamation is available via the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. It was published in the Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser on Wednesday, December 6, 1775.

What Lord Dunmore likely wasn’t expecting was the arrival of just as many women and children as men to fight. Desperate to escape the horrific reality of slavery, people traveled by night, alone or in groups, to answer the call of promised freedom.

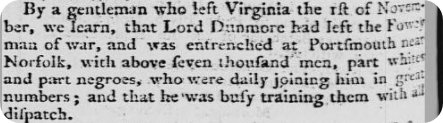

Caledonian Mercury, 9 December, 1775. View the full article.

While it didn’t result in a massive uprising, it did change the lives of hundreds of individuals forever. Only about 800 men were able to join the regiment. Many more were inspired to seek freedom behind the British lines over the course of the war.

Many saw battle. After weeks of hard labor building entrenchments, they went into the fight untrained, completely unfamiliar with their weapons and very short on ammunition.

Unfortunately, many of the Ethiopian Regiment died during the first year, mostly from smallpox. Others were returned to their former masters.

The Battle of Great Bridge was the only notable battle they were engaged in. It took place in early December 1775 and proved a very unsuccessful campaign for the British. After eventually being pushed out of mainland Virginia, Dunmore’s army sought safety at Tucker’s Mill, on flotillas at sea. Eventually, they found sanctuary at Gwynn’s Island off the east coast of Gloucester County.

Here, many more attempted to escape slavery and join Dunmore and his men. On the island, they suffered through a typhus epidemic, starvation, smallpox, dehydration and fire. Over time, the group split into two. One body headed for the relative safety of British-held New York, and the other for St. Augustine in Florida.

For those that did survive the war, some were part of the Black Loyalist movement that migrated to Nova Scotia, Canada. An even smaller percentage made their way to other British territories, or to Britain itself. Some likely became part of the Sierra Leone movement in the 1800s.

In 1779, British General Sir Henry Clinton issued the Philipsburg Proclamation. It freed slaves owned by colonial revolutionaries, even if they did not enlist in the Army. It’s estimated that up to 100,000 enslaved people attempted to leave their owners and join the British during the war.

At Findmypast, we’ve developed an index of what is known of these individuals from several different sources. It’s published and searchable online in Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, 1776. While the information on many individuals is scarce, this is an ongoing project that will see more records added as new historical accounts are identified.

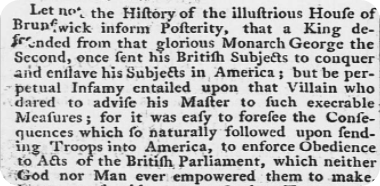

Perhaps one of the biggest issues facing the Continental Congress and the new country of America was the question of slavery. Leading up to and during the Revolution, the Patriots were fond of publishing rallying cries, such as;

"“don’t become a slave to the British tyranny.” "

The irony of such a claim, while enslaving others at the same time, is monstrous. Historians generally agree the issue of slavery was one that could have torn apart the Patriot cause altogether.

An oration delivered by John Hancock recognizing the 4th anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Derby Mercury, May 27, 1774. View the full article.

The question of slavery was one of the most debated and difficult to come to terms with in America at the time. We know now that the issue would continue to be a significant one for the American people. It would lead to the American Civil War approximately 100 years after the creation of the country. Ultimately, more American slaves found their freedom through the Revolutionary War proclamations than any other means until the Civil War.

Around 1,200 runaway slaves responded to Dunmore’s call to bear arms and support the King. Compared to the 200,000 enslaved people in Virginia at the time, it may not appear to be that significant. But these events represent a monumental sacrifice. One that allowed individuals who were systematically denied the ability to make their own decisions, to do just that.

Charles W. Carey, Jr summarizes it best in his 1995 Thesis on Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment. In it, he refers to founding father, Patrick Henry and his famous declaration to the Second Virginia Convention in 1775;

"“When Patrick Henry delivered his immortal demand for either liberty or death, he was not speaking to slaves. No matter; they heard him anyway. And those who could, responded to his call. They endured the cold and the mud, hunger and thirst, disease and deprivation, to fight untrained against a numerically superior foe.” "