Understanding Irish migration patterns in your family tree

6-7 minute read

By Brian Donovan | January 27, 2025

When researching Irish genealogy, it's crucial to understand the historical context. Brian Donovan takes a deep dive into the movement of Irish people across the globe, from the Norman Conquest to the present day.

Over Ireland’s history, famine and hardship has forced countless families to make heartwrenching goodbyes, as loved ones travelled overseas to chase new fortunes in foreign lands.

The Irish story is one of migration and resilience. This is reflected in a fact that may surprise you: more people of Irish heritage live outside of Ireland than within it. Over 80 million people worldwide claim Irish ancestry.

Whether they fled the devastation of the Great Famine or sought out religious freedom overseas, your Irish ancestors may have been part of one of the many historical migrations of the Irish nation and its people. To understand their experiences, we must delve deeper into the world in which they lived.

Irish migration in the Medieval period (c. 500- 1500 AD)

In the early medieval period, Ireland was the centre of two pursuits. These were:

- The expansion of Christianity across Europe

- Irish Kingdom expansion into Scotland and Western Britain

Both projects entailed Irish immigration overseas, across the European continent and into Scotland and modern-day England and Wales.

There was also significant immigration into Ireland over this period. Vikings – Scandinavian raiders, traders and settlers – also markedly impacted the Irish population, particularly on the eastern and southern coast. Vikings brought allies, servants and slaves from across Britain, especially the Hebrides in Scotland.

Between the 8th and 11th centuries, our Irish forebears lived lives that we can barely imagine today. The Viking invasion put coastal communities at risk – families who lived near the water spent their days terrified of raids, which brought with them the very real possibility of kidnappings, and being sold into the slavery which underpinned the Viking economy.

Our pious ancestors may have found their faith under attack. Because they were hubs of wealth and learning, Irish monasteries were often looted and destroyed by the Vikings – leaving ordinary Catholic worshippers robbed of their holy sites.

Alongside the terror and violence, the Viking invasion brought new culture, technologies and trade alliances to Ireland, changing the face of the nation forever. Many new towns were founded. It is claimed that Dublin became the busiest slave market in northern Europe in the 10th century, which carried many Irish out to other parts of the Viking domains from Greenland to Russia.

The Anglo-Norman conquest of Ireland in the years after 1169 also brought a significant influx of Anglo-Saxon, Flemish and Welsh groups under their Norman leaders. These immigrants settled in large numbers in the east and south of Ireland.

Scottish mercenary warriors (the gallowglass and redshanks) also came to bolster the forces of Irish lordships in their confrontations with their rivals, be they Anglo-Norman or Irish.

Irish history in the early modern period (c. 1500-1800)

Over the early modern period, Ireland experienced three conquests – the Tudor, the Cromwellian and the Williamite. There were several forced population transfers, to Sweden, the Caribbean, and from the east to the west of Ireland.

These combined factors drove outward migration between 1500 and 1700, with around 200,000 people leaving the country either forcibly or to escape dire circumstances. Alongside this migration, huge swathes of Ireland’s land were confiscated and handed to English and Scottish landlords. Exemplified by Ulster, these landlords were often required to rent their land to British tenants.

Protestant settlers in Ireland

More than 200,000 mostly Presbyterian Scottish settlers arrived in Ireland between 1610 and 1700, concentrated in the north-east of Ulster. They were followed by other Protestant migrants, including roughly 5,000 French Huguenots after 1685 and 3,000 German Palatines from 1709.

While the authorities thought that settling more Protestants was desirable in Ireland, they were generally not Episcopalians, like the established Church of Ireland.

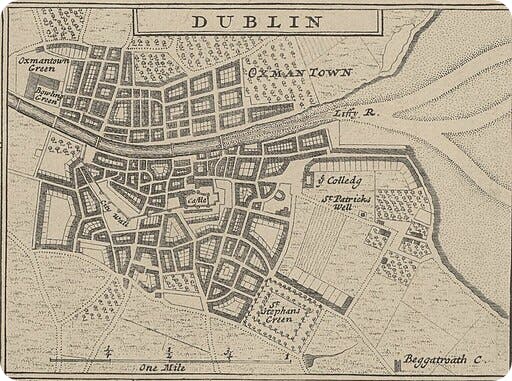

A map of Dublin in 1714.

They were often subject to discrimination in land ownership and occupations and were precluded from public office and the right to vote. Your Protestant ancestor may have been stripped of his democratic right to vote during this period. He may have had his land claims denied, causing his family to suffer the sting of poverty due to religious discrimination.

This treatment prompted many to leave for the less restrictive environment of North America, where they are generally remembered as the Scots Irish.

From Navan to New York...

More Irish emigrants came to America from the south and east of the country than Ulster at this time. They tended to be English speakers and had conformed to the state religion, but they were of mixed backgrounds.

They quickly merged into the mainstream colonial American community and are far less visible to genealogists researching today. This should not be a surprise, as at this time Dublin was the second key city of the fast-growing British Empire.

There were plenty of opportunities available in a variety of countries and occupations, especially for those who spoke English and had enough money to make the journey. By 1800, around one million Irish people had travelled abroad.

Irish immigration in the 19th century

Irish people found many opportunities available to them within the British Army. Throughout the 19th century, as the armies of the British Empire conquered countries across Asia and Africa, there were always Irish men in their ranks.

Interestingly, the British also favoured Irish Catholic churchmen being installed in countries that were the former colonial possessions of the French, Portuguese and Spanish. This religious route was another path taken by many Irish immigrants in this period.

The main driver of migration in this period was economic. After the Act of the Union in 1800 relocated much of Ireland’s wealth to London, the lack of industrial investment meant there was a shortage of jobs. The growing Irish population migrated in large numbers to the mills, factories and mines in England and Wales, or further afield in North and South America.

The impact of the Irish Famine (1845-52)

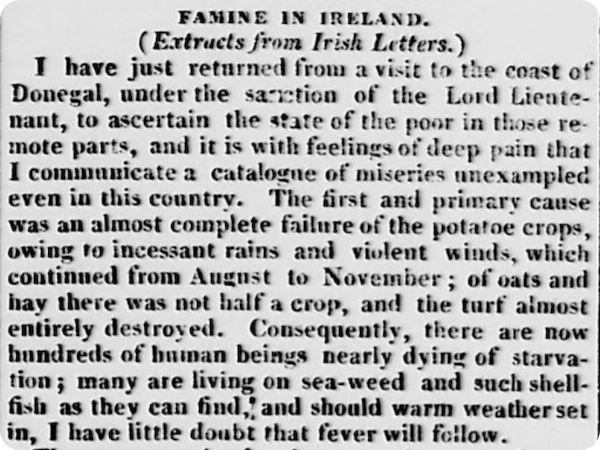

Over seven years, more than one million people died because of the tragic Irish famine. A further two million people left the country altogether, travelling mostly to North America and Britain.

A letter in the Leicester Journal reporting on the Irish famine. Read in full.

By 1855, over 33% of the Irish population was dead or had migrated. In the modern day, there are still fewer people on the island than there were in 1841 - a haunting reminder of the famine’s colossal impact on Irish society, politics, and culture.

Families clutched meager belongings as they boarded overcrowded, state-sponsored ships bound for Liverpool or Canada. The lucky ones, those with funds or recipients of aid, purchased tickets to America. By the early 1850s, cities like Toronto and New York were overrun with Irish arrivals, their streets alive with unfamiliar accents, bustling crowds, and the promise of new beginnings.

Find out if your ancestors experienced the Irish famine.

What happened after the 1850s?

After the famine, Ireland’s population steadily declined as more men, women, and children sought better lives abroad. Britain encouraged migration to Australia and Canada, while steep passage costs made migration to the US a gradual process.

Through ‘chain migration,’ families sent an eldest child first, who earned money to bring over siblings one by one. The youngest often funded their parents’ journey, if they were still alive to make it.

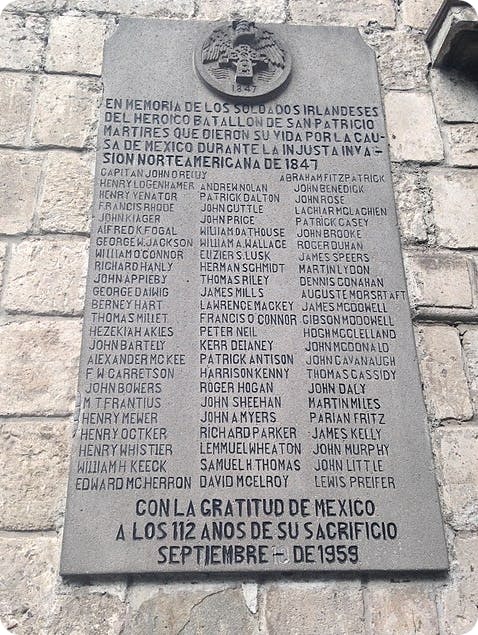

While the United States was a favoured destination, 100,000 Irish people also migrated to Argentina, Colombia, Chile and elsewhere in South America. Many more chose to migrate to Mexico, as evidenced by the existence of the Batallón de San Patricio – a largely Irish battalion in the Mexican Army that fought against the US between 1846 and 1848.

Memorial to the Batallón de San Patricio. Image credit: Raulchm, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Britain re-emerged as the favoured destination in the early 20th century, when US immigration rules tightened. Until the 1990s, most Irish immigrants chose either Britain or the United States as their new home.

Around six million Irish people emigrated from 1855 to 1920 alone, with another 500,000 moving in the 1950s.

They often endured dirty, cramped ship conditions for weeks. Upon arrival in England and the United States, they faced racism and discrimination on multiple fronts. Businesses displayed signs that read ‘No Irish Need Apply’ - our Irish ancestors were often shut out of skilled professions, instead remaining trapped in the poverty that had driven their move overseas.

Understand your Irish roots with Findmypast

When it comes to uncovering your Irish heritage, Findmypast is unrivalled. With the largest collection of Irish family records available online, we offer you the best tools to navigate the unique challenges of Irish genealogical research.

Our user-friendly family tree builder makes exploring your Irish roots straightforward, even if you’re just starting out. And if you’ve hit a roadblock, we’ve got you covered. From expert advice on Irish surnames to in-depth tips for exploring Irish newspapers, our comprehensive resources will guide you every step of the way.

Ready to discover your Irish story? Findmypast is here to make it happen.