1920s style: class, controversy, and liberation

8-9 minute read

By Jessie Ohara | October 11, 2022

You've heard of the Roaring Twenties, the Flapper Era, the Golden Times - but what of 1920s fashion? In a time often dubbed to be some of the most progressive years in international history, let's take a closer look at the styles of the season.

Between the lipstick revolution, the new-found popularity of the bob, the suited-and-booted style of the working men, and the incomparable influence of Hollywood on fashion, the 1920s saw style changes that were entirely unprecedented.

A history defined by the pout

As women found themselves with more everyday freedoms in the 1920s, and as they began to slowly shirk the implications of being a woman within the systemic social hierarchy, their makeup became brighter, bolder, and more daring.

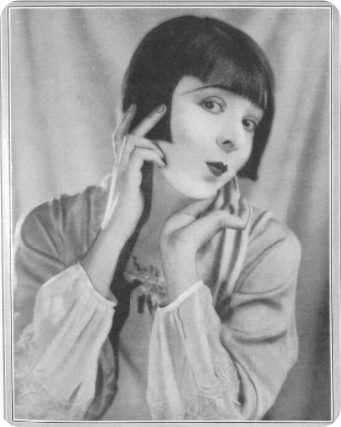

A woman peers into her mirror in The Sketch, 1928.

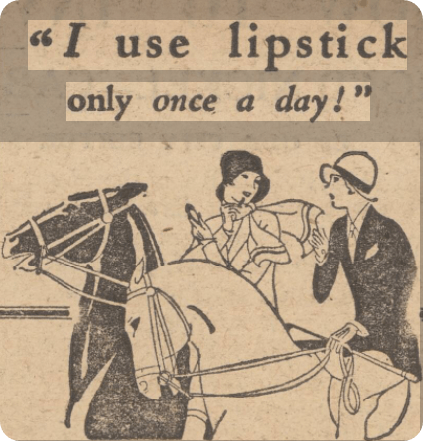

The power of lipstick began to grip the women of the decade. Decadent illustrations of women peering into their compacts and touching up their pouts accompanied a myriad of daily adverts, selling lipsticks that were waterproof, smear-proof, and most importantly - kiss-proof. It was with this selling point that the rouge tones of women's mouths became a symbol not only for their newly expanded social freedoms, but their newly expanded sexual freedoms - the implication of course being that with kiss-proof lipstick, who's counting how many boys are graced with a peck or two?

An illustration in The Daily Mirror, 1928.

In 1928, a Daily Mirror advertisement began:

""My dear, I've discovered the most amazing new Kissproof lipstick! I put it on once in the morning and know my lips will look their loveliest all day long, no matter what I do!""

Of course, just as is the case a century on, the use of heavier women's make-up had its critics. Amongst an abundance of articles that condemn lipstick for its chemicals, its physical effects on the digestive system or even the danger of poisoning, lies a thinly-veiled distaste of the contemporary woman's use of the product. Consistent references to its artificiality and gaudiness barely hide the true subtext - that this small facet to women's liberation was certainly not universally celebrated.

An excerpt of an article in The Daily Mirror, 1929.

However, just as with all forms of contemporary contention surrounding women's appearances, lipstick always had its defenders: Lady Kitty Vincent writes for the Leinster Reporter in 1928:

""If Providence intended us to have scarlet lips we should have been born with them." we are told by objectors. We are not born with clothes, so evidently Providence leaves something to our own initiative.'"

It is since this time that lipstick has never truly gone out of fashion, though its shades and colors have varied season to season. There is no doubt that while the popularity of lipstick may have only been symptomatic of a wider cultural shift, it absolutely contributed to the beginning of a social revolution.

Short skirts, shorter hair

If there was any doubt that women's changing appearances was - and still is - conducive to their social and sexual liberty, an article in the Banbury Adviser written in 1926 makes the connection with vigour.

""Sex equality has largely abolished sex self-consciousness, and flippant flirtations between voting people are much less evident than they were in the days when a girl's outlook on life was limited to parlour accomplishments""

Given that this article is titled 'mixed haircutting', the perceived parallels between short hair and social equality become clear. The author goes on to say:

""Were it otherwise, it would not be possible for women and girls to take their turn with men for hair trimming in the men hairdressing establishments... What makes it popular is that in these establishments women pay no more for a hair trim than men do.""

Bob cuts, shingling, finger waves and the 'Eton cut' truly came into fashion for 1920s women. They were more practical for domestic duties, workplaces should they have them, and most importantly - dancing. Unlike the controversy behind the lipstick craze, some articles even claimed it was one of the most important steps forward in the increase of women's health of their time. One article went so far as to claim that the 'cleanest long hair in the world stands in constant danger of being infected by this great agent of disease and death.'

A woman with a shingled coiffure, pictured in the Leeds Mercury, 1923.

Whether or not this is true - and we suspect it is not - does not change the fact that with shorter hair, women were more free to work and play as they pleased. Gone were the days of long flowing locks symbolising a woman's purity, and instead came the days where a woman's hairstyle symbolised her expanding freedoms as an independent citizen.

An excerpt from an article in St Andrew's Citizen, 1925.

Again, of course, the trend wasn't without its criticisms. As the above article notes, some vilifiers masked their misogyny with insubstantial claims that short hair made women lose their individuality, or that they all looked the same, before launching into a tirade that claimed the short hair trend came hand-in-hand with the masculinization of women. Within this, of course, lies the implication that women were less passive and more outspoken:

""Women, they declare, are not only becoming geometrical but masculine in mentality, and rebellious against the emotional and sentimental traits of the old femininity.""

This specific article concludes by refuting this claim, but it is clear that the same social issues revolving around women's makeup are mirrored almost exactly in their choices of hairstyle: women were becoming less easy to control, and such image changes represented the threat they posed to contemporary masculine ideals.

And what of the men?

Inevitably, men's fashions are not nearly as debated and speculated as women's, and while there is a point to be made about such a disparity, men's 1920s style is not one to be ignored. Tailored suits were at the forefront of such fashions.

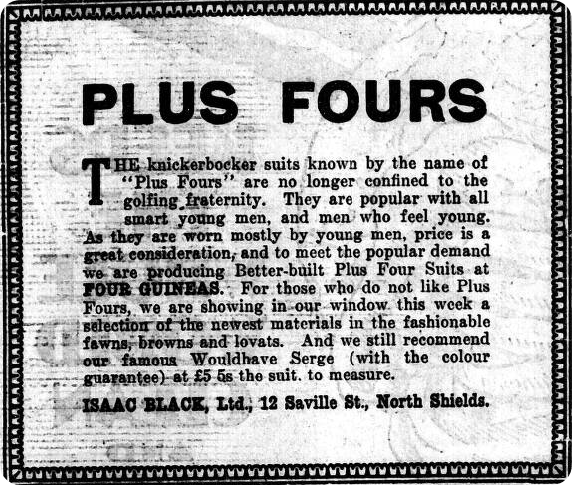

A snippet of an article in the Shields Daily News, 1925.

This is not to say that men's fashion had not evolved. Plus Fours, a form of breeches that came less than four inches past the knee, were popularized from sports-players and athletes into the more general male public. They offered more freedom of movement, a looser style, and more comfortable wear, tying in with the social ethos of the 1920s: a way of life that was more free, and more careless, than previous eras.

A boy in Plus Fours, in the Aberdeen Press and Journal, 1923.

Wearing a hat was also a daily exercise in men's fashion. Newsboy caps - as seen in Peaky Blinders - were most popular amongst younger boys and the poorer classes. The middle-class men tended towards bowler hats or derby caps, and formal occasions saw top hats emerging from the wardrobe.

A man pictured in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 1926.

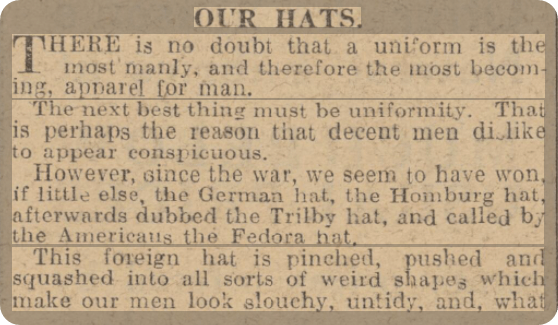

Interestingly, the 1920s also saw the male adoption of previously female-coded items - the fedora, a hat that was solely worn by women in the 1800s, saw a huge boost in popularity amongst men, and was often worn by the middle-classes for business affairs. Like most women's fashion - and indeed, most trendy fashions in general - it wasn't without it's criticisms.

A snippet from the Daily Mail, 1924.

The above article, found in the Daily Mail in 1924, notes that while uniformity is an inherent signifier of masculinity, the fedora hat is not a trend that should be popular within the male population. For starters, it originated in Germany - suspicion around its trendiness was inevitably linked to the disdain for the Germans after World War 1. The article goes on to claim:

""This foreign hat is pinched, pushed and squashed into all sorts of weird shapes - which make our men look slouchy, untidy, and what is worse, dirty.""

Clearly, while men's fashions were less speculated than women's, there was still some contention around the origins of certain trends. The article concludes:

""What is the matter with good old British style for the British?""

Just as is the case with women's fashion, this is an argument that rings true even in our modern times - and debates around non-native styles, looser clothing, sexual liberation, and comfortability still persist even now.

Androgyny on- and off-screen

What all of these fashions began to leave behind was the staunch gender disparity of the Victorian era. Ineffably tight-waisted corsets, flouncing petticoats, virginial long locks, the severe tailoring of suits were all aspects of a strict binary framework that separated the 'masculine' and 'feminine' in the most overt of ways - that is, until the 1920s trends shifted public opinion. While these changes were not smooth, and while there was an abundance of condemnation, the trends persisted. Flapper dresses were looser, more boy-ish, and women often mixed their lace and chiffon with the ease of linen and cotton; men began to venture into more oversized, easy-fitting trousers, growing shorter as the years went by.

'The Perfect Flapper' pictured in The Tatler, 1924.

This was fully affected, and reflected, by the women witnessed in the ever-growing Hollywood industry. In 1927, Dorothy Mackaill starred in feature film The Crystal Cup, wearing a sharp tuxedo suit most often seen on upper-class men, and acting in a way that was outspoken and independent. The Kinematograph Weekly noted:

""Dorothy Mackaill is attractive in feminine attire and acts cleverly in mannish clothes.""

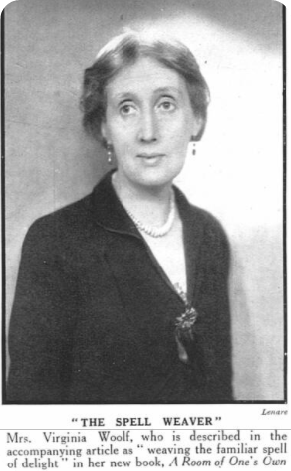

It doesn't end there, of course - Katherine Hepburn was in a group of post-suffragette women, and even confessed later in life that she sometimes wished she was born a man for the sake of his freedoms; she went on to perform as a woman who cross-dressed as a man in order to escape the police. Virginia Woolf's book Orlando, published in 1928, documents the story of a man who wakes up as a woman, after a sleep that lasts over a period of days. Now, it is studied as a classic piece of feminist and transgender literature - though perhaps more interestingly, it was a huge success at the time of publishing, and consequently guaranteed Woolf's financial stability as an author.

Virginia Woolf as pictured in The Graphic, 1929.

What these newspaper snippets evidence, most of all, is that the changes in fashion in the 1920s held a mirror to the changes in national and social identity, particularly that of women. There were parallels drawn between women's fashion and women's mannerisms, issues of contention around the use of foreign styles, changes in fabric, fit and frames of mind. It was nothing short of a revolution - one that still ripples through to our modern day trends and principles.

The 1921 Census paints a bolder picture of life in the 1920s, with fashion and style only being one aspect of its greatness as a decade. Learn more about what life was like, and to unlock your own family mysteries, get unlimited access to the 1921 Census with a Premium subscription.