Understand your Irish roots with these books and top tips

7-8 minute read

By Brian Donovan | February 24, 2023

In-house expert Brian Donovan discusses his favourite publications for understanding the circumstances that surround generations of Irish migration.

Bitter religious conflict. Economic hardship. Land dispossession. A thriving literary and musical culture, and the endurance of strong family ties. Ireland’s history is made up of dramatic episodes and strong community spirit alike.

Our Irish ancestors' lives were full of ups and downs – from the joyous baptism of a new family member to wartime deaths and looming poverty, they lived through life events, big and small.

Although less than seven million people live in Ireland, more than 90 million people globally claim Irish ancestry. This huge number highlights how central travel and migration have been to the lives of the Irish people over the years.

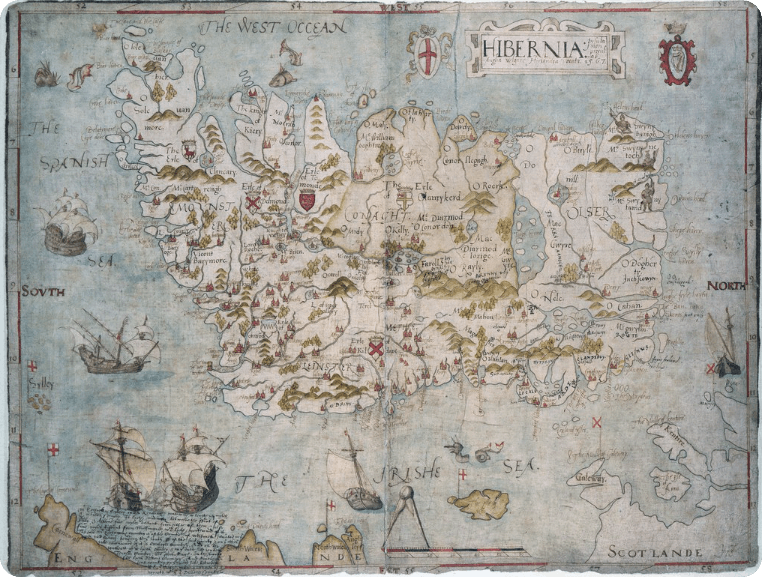

A 1567 map of Ireland by John Goghe.

The story of how the Irish diaspora came to span the globe is a multi-layered one which spans centuries. You may be familiar with one of the many migrations from Ireland - the flight during the Great Famine (1845-52) - which saw up to a third of the population flee amidst widespread starvation and poverty.

Search Irish records

The Famine is just one thread in the tapestry of the Irish diaspora - millions of varied lives, with family legacies spanning generations, make up the diaspora’s history.

In one way or another I have been studying Ireland’s historical migrations all my life, including helping set up EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum in Dublin in 2016.

EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum, Dublin.

Many years ago, I digitized the wonderful 1890 edition of The Irish Emigrant's Guide for the United States (available free at the Irish Family History Centre), a practical guide for those arriving in America. It describes how to secure employment on arrival, get a bank account, find accommodation, and more including notes on each individual state.

It's extraordinary reading the actual guidebook that immigrants used to get started.

Contemporary sources to understand Irish diaspora

There has been a huge amount of scholarship around Irish migration to America. In 2006, Glucksman Ireland House, NYU, picked apart the various themes of Irish migration to America and the subsequent Americanization of the Irish in Making the Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States, edited by Professors Joe Lee & Marion Casey.

Making the Irish American book cover.

It’s a big book, packed with specialist articles on the Scots-Irish, Presbyterians, Catholicism (Irish and American) and religious rivalry between and within the community. It discusses the place of the Irish in the labor movement, politics and the impact they had on Irish nationalism both in the US and back at home.

But despite dealing at length with the positive stories of Irish involvement in music and sports, the book does not flinch from the darker side of the Irish experience, including the bigotry they were faced with and the frequent bouts of racist violence they perpetrated on others.

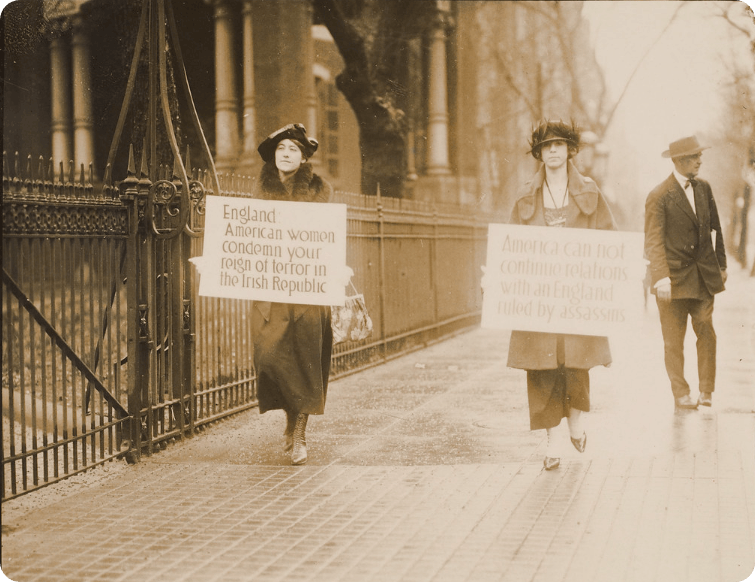

Two American-Irish women protesting England's treatment of the Irish at the British Embassy, Washington, 1920.

While Irish migration to America is universally acknowledged, the most likely destination. The Industrial Revolution desperately needed labour, and the Irish answered that call in droves. It has been estimated that today 1 in 4 people in Britain have an Irish grandparent.

We can imagine what our Irish grandparents and great-grandparents would have experienced as they upended their lives to settle across the Irish sea. Often arriving penniless with just the clothes on their back, they faced racism and discrimination upon moving to growing cities like Liverpool.

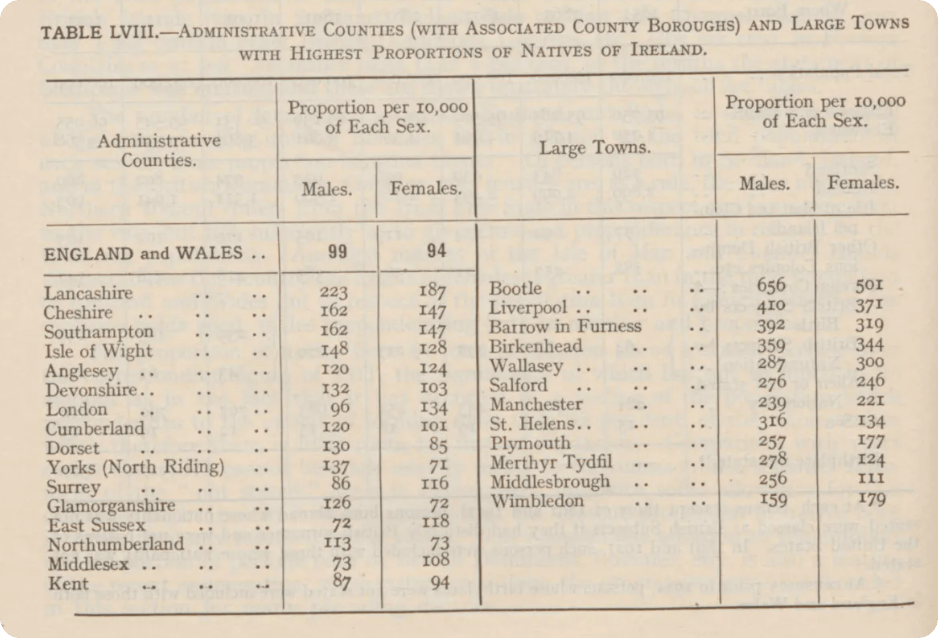

A table showing the counties with the largest proportion of Irish residents, as reported in the 1921 Census of England and Wales.

Unlike those that settled in America, the Irish that spread roots in England, Scotland and Wales tended to lose their national identity quicker, and more rapidly merge with the communities they settled amongst.

This - and much more - is comprehensively covered in the excellent book by Professor Donald MacRaild, The Irish Diaspora in Britain 1750-1939 (2nd edition 2010), who elegantly summarizes and collates the research that has been published across hundreds of specialist studies.

The Irish Diaspora in Britain 1750-1939 book cover.

Unusually, he also address the Irish Protestant community and showed how they maintained a separate identity.

As well as this, his work shows how much the story has improved from the Catholic nationalist nostalgia evident in older works, like John Denvir’s 1892 book The Irish in Britain: From the Earliest Times to the Fall and Death of Parnell (available free on archive.org).

Irish settlement worldwide is also part of the uncomfortable story of the British Empire. Ireland was, after all, a constituent part of the United Kingdom from 1800, and politically controlled by Britain for centuries before that date.

A photograph of barracks in a British Army garrison in Munster, Ireland, taken in the early 1920s.

Uniquely, the Irish story is both as victims and perpetrators of Empire. Naturally, we feel more comfortable with the former than the latter, but both sides are equally true.

This is explored with great depth and nuance in Nicholas Canny’s first chapter in Kevin Kenny’s masterful Ireland and the British Empire. Keith Jeffery’s comprehensive volume of essays, ‘An Irish Empire’?: Aspects of Ireland and the British Empire delves ever further into these complexities.

Ireland and the British Empire book cover.

Reading these, I quickly realized how messy the Irish entanglement in Empire was, made even more complicated by the active British promotion of the Irish Catholic church in their colonies as a loyal ally. This is revealed in Colin Barr’s, Ireland’s Empire: The Roman Catholic Church in the English-speaking world, 1829–1914 (Cambridge).

As family historians, of course, we always try to understand these big themes through individual stories. But there are so many individual stories it can be difficult to know where to start. One book that sticks with me though is a volume of reports Mr. Tuke's Fund for Assisted Emigration 1882-5 (available free at the Irish Family History Centre).

The Irish Family History Centre, Dublin.

This was a philanthropic fund set up by the Quaker James Tuke to help over 9,000 people leave parts of the most impoverished regions of the west of Ireland to go to America.

Not only does the book list all the emigrants, their addresses in Ireland and where they moved to, but they also printed their letters home detailing what life was like in their new homes.

One wrote from Ontario, Canada:

"I was only twenty minutes at the hotel before I was engaged on a farm. Wages are big here; this is a fine country. Spring is just commencing. My parents have got a house here, and father is working on the railway."

Letters and personal memoirs are also the focus of a modern scholarly work by Kerby Miller, Irish Immigrants in the Land of Canaan 1675-1815, on the earlier period of migration to America, more likely from the eastern half of Ireland.

The American Committee for Relief inspecting the ruins of Balbriggan in eastern Ireland, c. 1921.

But the book is far more than a collection of interesting historical documents. Instead, Miller uses the documents as a touchpoint to address a range of big social questions, settlement patterns, and political issues.

More importantly, the book transformed our understanding of the scale of Irish migration in the 18th century, showing how more than 400,000 arrived.

Remembering historical Irish migrations

Irish immigrants, like those from any other country, had much they did not want to remember and little time to put their own experience in any sort of context. In that case, it is up to family historians to recover the individual stories and place them into the flow of the migration story from Ireland using Irish records and historical newspapers.

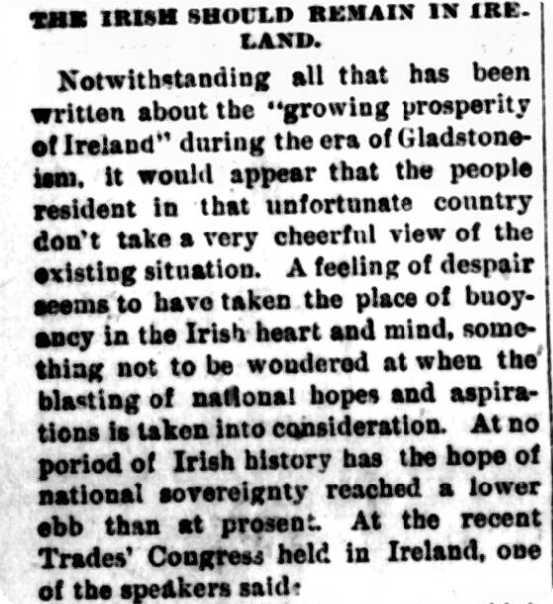

An article titled 'The Irish should remain in Ireland', published in American-Irish newspaper the Chicago Citizen, 1895.

If you want to learn more about researching Irish genealogy, why not delve into the top five books that inspired our Catholic Heritage Archive?

Findmypast has a huge collection of Irish records, including Roman Catholic church registers and historical Irish newspapers spanning hundreds of years. You can search Ireland's earliest surviving census records (1821-1851), Irish Petty Sessions and Poverty Relief Loans 1821-1874.

Our records can help you chart the joyous moments and immense struggles that your Irish ancestors experienced. Delve deeper with these valuable sources, and piece together a vivid picture of ordinary people living extraordinary lives.

To uncover our collective heritage in fascinating detail, why not explore our full list of Irish family history records?

Tracing Irish ancestors: FAQs

How do I trace Northern Irish ancestors?

You can trace the Northern Irish branches of your family tree using Findmypast. Our Belfast & Ulster Directories and Northern Irish newspapers may be useful when searching for family from Northern Ireland.

How far back do church records go in Ireland?

While the Church of Irelands records go as far back as 1536, a third were tragically destroyed in a fire at the Public Record Office of Ireland in 1922. But with historical newspapers, extensive records that survived and our intuitive family tree builder to help you, Findmypast can help you to overcome the trickiness of researching Irish genealogy.