From public intoxication to petty theft, here are our top 5 books for researching criminal history in your family tree

4-5 minute read

By Aoife O Connor | January 9, 2023

Findmypast's genealogy expert Aoife O Connor shares her top recommendations for budding criminal history researchers.

Finding an ancestor who broke the law can be a surprise; it can raise lots of questions about the circumstances that brought them to court or prison. When imprisoned for a crime we would consider minor today, it can also make us wonder about how the law operated in the past.

Criminal justice records are some of the richest we can find.

They contain information not just about the crime our ancestor was accused of or served time for, but also details such as their height, eye colour and any scars they might have. Many later records even have photographs.

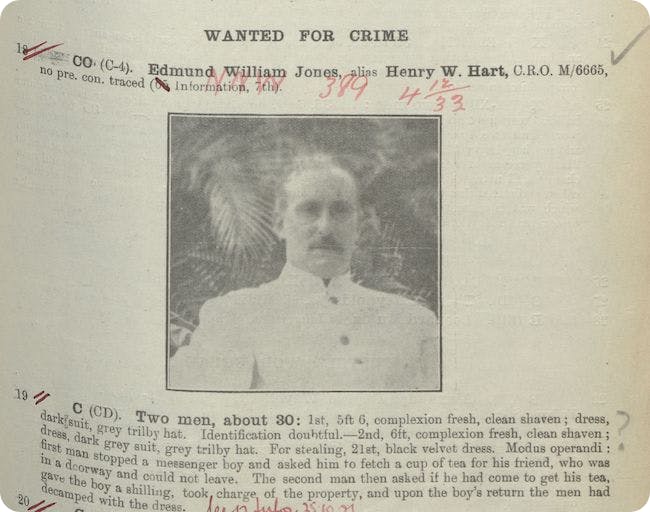

The 'Wanted' notice of Edmund William Jones, 22 October 1921. View the full record here.

Take the record above as just one example. This source from Findmypast's England & Wales, Crime, Prisons & Punishment record set includes an image of Edmund William Jones, who also went by the name Henry W. Hart (presumably to evade the authorities). It provides rich insight into criminality in 1920s Britain.

Here at Findmypast, we have millions of records relating to the criminal justice system. We could likely all find an ancestor in our family tree who broke the law. The information associated with our Irish petty sessions and other criminal records can help you to understand more about the specific records you discover.

Like Edmund William Jones, maybe one of your ancestors can be found among those 'Wanted' for a historical crime.

Our top criminal history picks

To take your research further by learning more about the criminal justice system, we recommend the following books.

1. Tracing your Criminal Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians by Stephen Wade

Published in 2009, Stephen Wade’s book predates the digitisation of many of the larger criminal justice record collections. As such, it makes no assumptions about what will be available to you and guides you through an understanding of all of the major record types.

More recently, Stephen Wade has published Tracing Your Prisoner Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians.

2. Criminal Children: Researching Juvenile Offenders 1820-1920 by Emma Watkins and Barry Godfrey

In the 19th century, the law applied to everyone. Children as young as seven years old (or younger) can be found in prison records.

In the early nineteenth century, children could be transported to Australia, while later in the century, they were sent to reformatories. Many children in this period found themselves imprisoned.

One of the more recently published books on the topic, Criminal Children, combines research techniques with illustrative stories to explore the world of young offenders in the long nineteenth century.

If you have a specific interest in juvenile crime, it is also worth picking up or requesting via library loan Fagin's Children: Criminal Children in Victorian England by Jeannie Duckworth. You'll no doubt also find useful Heather Shore’s Artful Dodgers: Youth and Crime in Early Nineteenth-Century London.

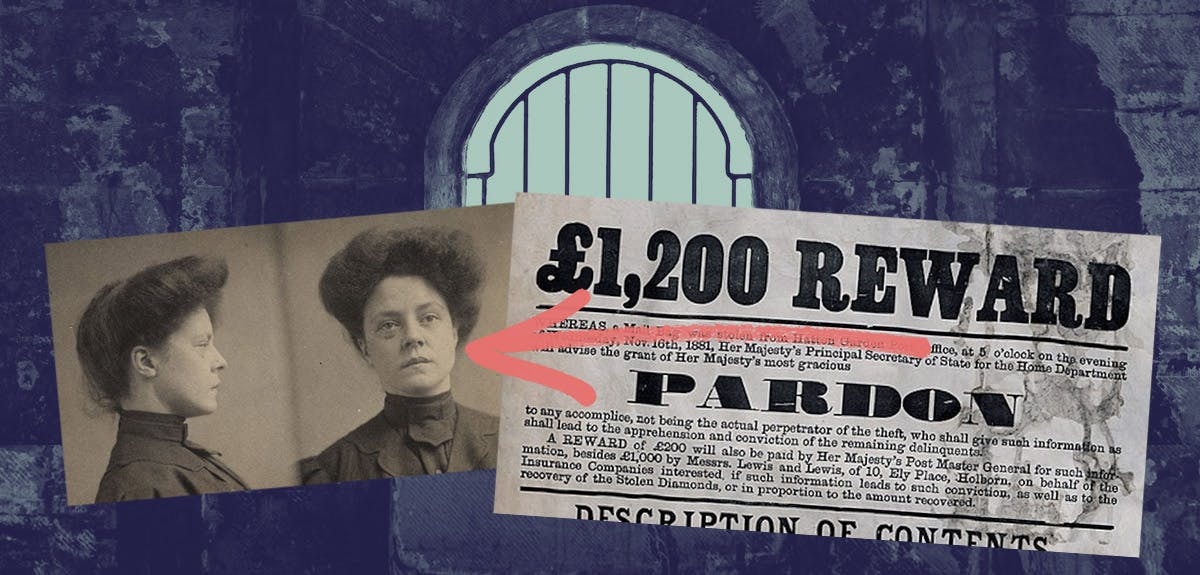

3. Criminal Women 1850-1920: Researching the Lives of Britain's Female Offenders by Lucy Williams & Barry Godfrey

According to this book's authors:

"'Women are among the hardest individuals to trace through the historical record, and this is especially true of female offenders who had a vested interest in not wanting to be found'. "

While the determined family historian can usually discover even those who have tried very hard to fly under the radar, this book provides valuable insight into women's experience of the justice system.

It contains numerous case studies, which offer new avenues of research and open up new ways of thinking about our female ancestors who found themselves in trouble with the law.

4. Tracing Villains and Their Victims: A Guide to Criminal Ancestors for Family Historians by Jonathan Oates

Jonathan Oates brings proper attention to the victims of crime in his 2017 book. In tracing our criminal ancestors, we must not forget that their actions affected others, their victims, and indeed their family.

Oates’ book is a guide to resources and contains particularly useful descriptions of the various types of courts in England.

Here at Findmypast, we’re no strangers to the incredible resource that is newspapers.

As Oates points out, these are some of the best sources for researching both sides of a crime, although the language used can sometimes appear insensitive and we must always be alert to bias in newspaper reporting.

5. Crime in England 1815-1880: Experiencing the criminal justice system by Helen Johnston

If your interest lies in learning more about the justice system itself, this book is a good starting place.

Aimed at an academic readership, this book is an excellent introduction to the criminal justice system. It includes chapters on how the police force functioned, and how prisons small and large operated.

The book is particularly useful for understanding contemporary attitudes towards crime and criminals. As the introduction mentions, for much of the period under discussion, it was thought that:

"‘People became criminals because they were immoral, were poorly educated, lacked religion and were influenced by the examples around them – others in the community, cheap literature and low entertainment, as well as drink’. "

Learning about how the criminal justice system worked helps us understand why our ancestors were in court and prison for crimes that would be considered minor today.

Have you made a surprising discovery about criminality in your family tree? We'd love to hear about it. Share your family story with the Findmypast forum today.