Sole Survivor: Vivian Bullwinkel and the Banka Island Massacre

4-5 minute read

By Alex Cox | September 4, 2015

Over 3,400 women served with the Australian Army Nursing Service during World War II. Many of whom were sent to the Far East to offer medical support to troops fighting the Japanese. A number of these women were captured and endured the same brutal treatment and harsh conditions as male POWs. The stories of many these brave women can now be uncovered using our new Prisoner of War 1939-1945 collection.

Captain Vivian Bullwinkel was one of these women. She was born on December 18th 1915 in Kapunda, South Australia and, after training as a nurse and midwife, began her medical career at the Jessie McPherson Hospital in Melbourne in 1940.

In 1941, Bullwinkel volunteered to join the Royal Australian Air Force but was rejected for having flat feet. Undeterred, she then volunteered to join the Australian Army Nursing Service. Her application was successful and she was posted to the newly formed 2/13th Australian General Hospital.

In September that year, Bullwinkel and the rest of the 13th travelled to Singapore. At the time of their departure, the hospital was comprised of 18 officers, 44 nurses, 3 masseuses, 146 other ranks and was equipped to treat roughly 600 patients.

Japanese troops invaded Malaya on December 8th 1941. They swiftly advanced southwards and by late January were rapidly approaching the Bullwinkel hospital. The 13th AGH was subject to repeated bombing raids and was forced to operate under complete blackout conditions at night. The high number of mounting casualties soon overtook the hospital's ability to accommodate and treat them and patients and many were forced to lie on the lawns surrounding the hospital.

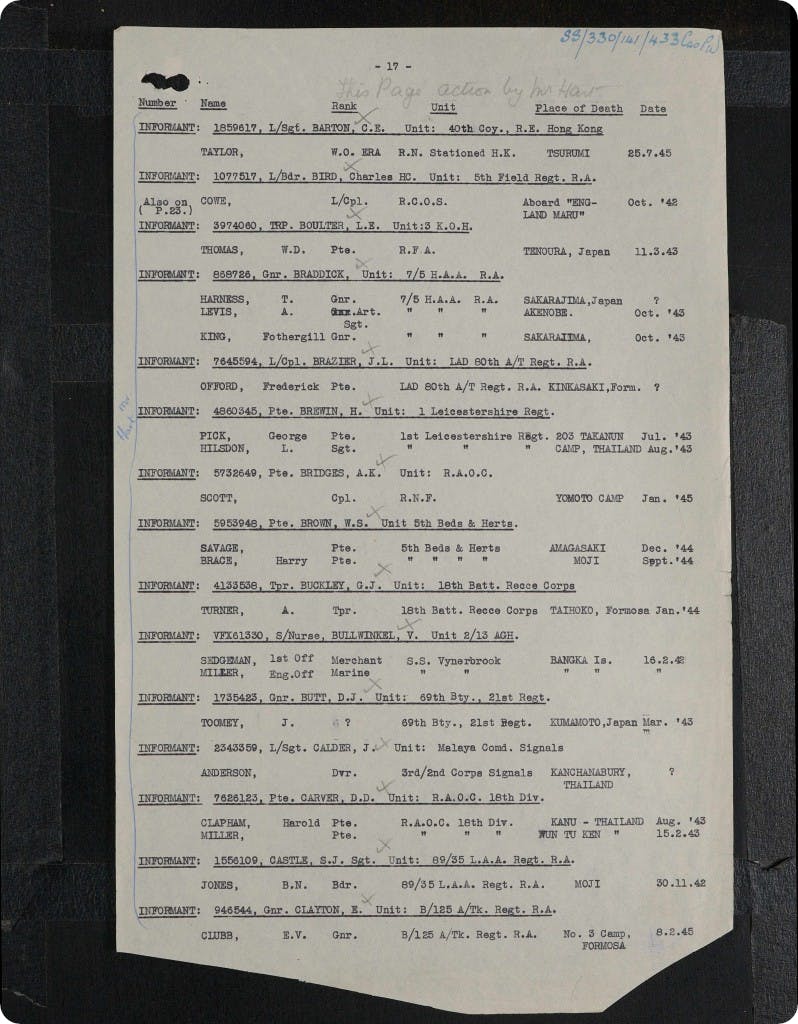

With defeat appearing imminent, the 13th's nursing sisters were evacuated on three ships. Bullwinkel was part of the last contingent of 65 nurses to be evacuated aboard the SS Vyner Brooke on February 12th.

On February 14th the Vyner Brooke was spotted by Japanese aircraft. Despite taking evasive action, she was crippled by several bombs and within half an hour rolled over and sank. Around 150 survivors eventually made it ashore at Banka Island, east of Sumatra, after periods of between eight and 65 hours in the water.

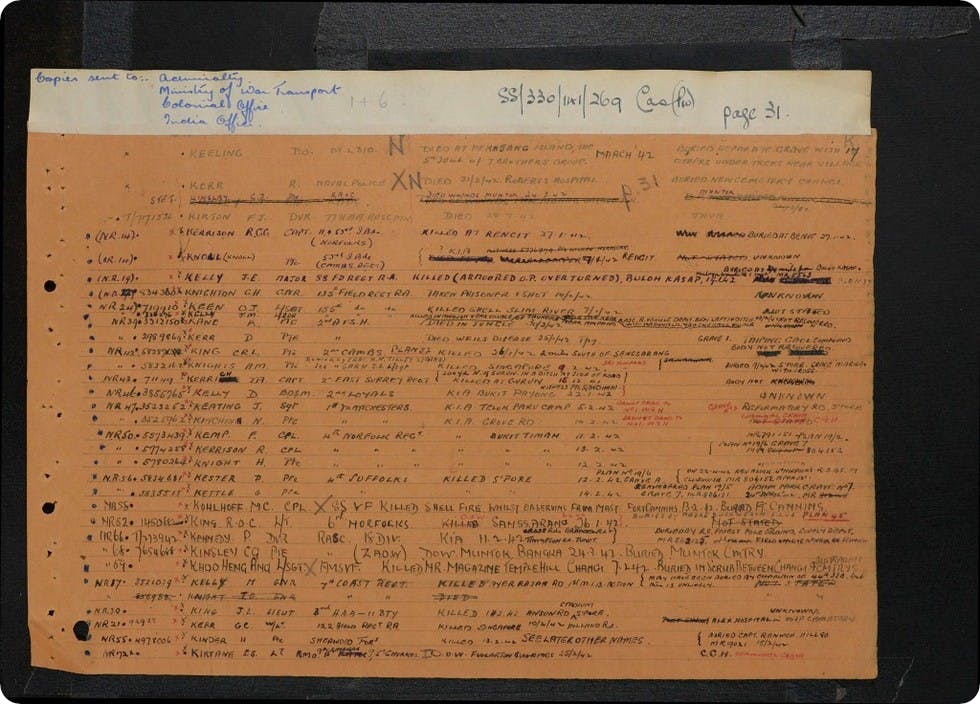

Bullwinkel, 21 other nurses and a large group of men, women, and children made it ashore at Radji Beach where they were joined the next day by about 100 British soldiers. The Island had already been occupied by the Japanese and many of the survivors had been captured during the night. Bullwinkel's group decided to surrender, and while the civilian women and children left in search of Japanese forces, the nurses, soldiers, and wounded waited on the beach.

Eventually a group of Japanese soldiers arrived. They shot and bayoneted the men without any hesitation and ordered the 22 remaining Australian nurses and one British civilian woman to wade into the sea, still wearing their grey dresses and Red Cross armbands. They knew what was to happen. Later in life, Vivian recalled how she heard their matron, Irene Drummond, say, as they moved through the water, "Chin up girls. I'm proud of you and I love you all." A nurse said drily: "There are two things I hate in life, the Japs and the sea, and today I've got both." Vivian saw no tears or signs of despair. When the women were up to their wastes, the Japanese raked them with machine gun fire from behind.

Bullwinkel was struck by a bullet high on her left hip. She was knocked over and allowed herself to float with the tide so as to appear dead. When she was eventually washed into the shallows, the beach was completely deserted. Bullwinkel was the only nurse to have survived.

As she walked up the beach she heard a feeble voice call out to her. It was the only other survivor of the massacre, a wounded British Army Private named Cecil Kinsley. Cecil had been bayoneted twice while layed out on a stretcher but had managed to crawl away into the jungle.

Bullwinkel and Kinsley spent the next 12 days hiding until the jungle. When it became apparent that they could not survive there permanently and Cecil's wounds were becoming badly infected, the pair made the difficult decision to attempt a second surrender.

They walked out of the jungle handed themselves in to Japanese troops. They were taken into captivity and Cecil was sent to a camp in Muntok in the in the Indonesian province of Bangka-Belitung where he died from his wounds within a few days.

Bullwinkel spent the next three and half years in captivity in a series of prison camps on Bangka Island and in Sumatra. She was initially forced to wear a water bottle on her hip to conceal her wound as the Japanese would have killed her immediately if it was discovered that she had survived and witnessed the massacre.

Of the 65 Australian nurses embarked upon the Vyner Brooke, 12 were killed during the air attack or drowned following the sinking, 21 were murdered on Radji Beach, and 32 became internees, 8 of whom subsequently died before the end of the war.

Vivian later gave evidence of war crimes to the Tokyo Tribunal. The Japanese officer thought to have ordered the massacre committed suicide; a camp commandant was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment.

In the decades following the war, Bullwinkel received many honours and awards, including the Florence Nightingale Medal, an MBE and the AM. She married in 1977 and returned to Banka Island in 1992 to unveil a shrine to the nurses who had lost their lives. Vivian Bullwinkel died on 3 July 2000.