My ongoing journey of reckoning with my enslaver ancestors

3-4 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | February 23, 2021

Findmypast's Jen Baldwin was forced to face her past when she discovered her ancestors had slaves. While disturbing, her story is important to tell.

Please note that the terms used in historical records reflect attitudes and language at the time and may now be considered derogatory or offensive.

There is a moment of reckoning, I think, that every family historian must face. It’s the moment of recognition when all evidence points to a part of history that reflects the worst of humanity. It’s different for all of us, but for me, this moment came when I faced the long-known – but largely avoided – truths of my maternal ancestors.

My maternal family had been in the State of Alabama for several generations, and before that, Virginia. We had collateral branches that reached Mississippi. There exists a strong possibility that the family arrived in the southern colonies quite early, stretching back to the 1600s. We fought in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. The truth I spent years trying to avoid, is that we also fought in the American Civil War, on behalf of the Confederacy.

My moment of reckoning, then, came when I was adding basic facts to my ancestor's timeline. Going through the motions of checking each federal census, finding the right household, and gleaning details from this routine process. I knew it was coming, but I still wasn’t ready for it. David Alexander Timberlake was born in 1833 and died in 1917, thus he was an adult living in his own home for the 1850 and 1860 United States Censuses and the corresponding Special Schedules.

Slave Schedules in census records

The seventh and eighth census of the United States included a “Slave Schedule,” in addition to the more commonly recognized Population Schedule. In these records, slave inhabitants were documented by listing the name of the owner, and a collection of several demographic questions:

- number of slaves

- their age, sex, and color

- whether they were a fugitive of the state, manumized, deaf & dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic

- the number of slave houses.

At no time does it ask for the names of these individuals.

In the 1860 US Federal Census Slave Schedule for St. Paul's Parish in Hanover County, Virginia, my ancestor - D.A. Timberlake - claims ownership of eight people. Ranging in age from 32 years to 3 years. Eight humans, whose lives were disregarded and disdained.

There are two other Timberlake households on that page of the census. Among them, 24 humans were considered property.

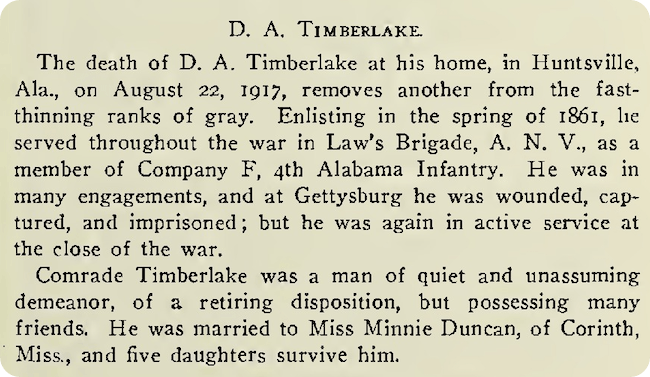

David Timberlake did serve in the Confederacy and was given the rank of Corporal. He lived out his life in Alabama, married, and they had five daughters. He received a veteran’s pension for his service, and his obituary was published in at least three regional newspapers and the Confederate Veteran’s Magazine. In all of this, his crowning achievement in life appears to have been his service for the Confederate cause. His name was added to a Confederate memorial in Huntsville posthumously.

David Timberlake's obituary in Confederate Veteran. Read the full article.

It appears that his father, and his grandfather, were slave owners, and most likely, several generations farther back. The evidence is there for us to see, in census schedules, property records, and wills and probate files. If you explore back to Harfield Timberlake, grandfather of David, you’ll find he left behind a large estate, including:

- James

- Warner, a boy

- Molly

- Harrison

- Reuben

- Sophia

- Hannah

- Old Tawney

- Margaret, a negro girl

- Winney, a negro child

...and many, many more. 29 in total.

For those keeping track, that’s a total of 53 souls bought and sold in just two generations of my family. And it doesn’t include the generations in between.

Everything I know of the Timberlakes, I learned through my family tree research. My mother was never willing to share much about her southern lineage, though she did discuss her German paternal heritage. She was raised in the tumultuous era of the 1950s and '60s in Birmingham, Alabama. She graduated high school the same year that Dr. Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., was writing his “Letters from a Birmingham Jail.” I do not know for sure if she was aware, as a teenager, of everything that was happening around her, or if she was sheltered from it all, but her hesitancy to discuss the family with me was as real as the fingers on my hand. I wish, now, that I had pushed just a little harder so that we could face the reality of our past together.

My moment of reckoning isn’t over. It’s one I relive every time I look at my family tree. It’s one that sits with me through every headline, breaking news alert, and moment of social unrest as the world around me continues to try to come to grips with our shared history and overcome it. I feel deeply that my responsibility as a human is to conduct thorough research and to share my findings broadly, so that others may find their ancestors; tucked away in the wills and census records of mine. It may be the most important research I ever do.

Telling the stories of our ancestors and ensuring they live on is often a source of inspiration for family historians. It is, also, a responsibility of ours to ensure that we do not allow ourselves to forget the mistakes we have made, the wrong paths we have chosen. Dare I say, it is our duty as citizens of the world to ensure that our ancestors’ actions – good and bad – are called out and if possible, corrected. We cannot change the past, but we can ensure that we take more steps forward to a better world today and in the future.