Discovering my ancestor had slaves has given me new perspectives on the past and present

3-4 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | February 8, 2021

Findmypast's Ben Bennett took an eye-opening but necessary journey of discovery to explore the impact of his enslaving ancestors. This is his story.

Please note that the terms used in historical records reflect attitudes and language at the time and may now be considered derogatory or offensive.

My third great grandfather on my mother’s side was Jordan Flake, born May 15, 1764, in Lilesville, North Carolina. He was a "planter" by trade and it was reported that by the age of 40, he had accumulated a considerable landed estate. Jordan had seven children, the first of which was James Madison Flake, born in 1815. James Madison was my second great-grandfather born in Lilesville in 1815. He died in Fresno, California in 1850.

In 1838, James married Agnes Haley Love in North Carolina. It's reported that as a wedding present from Jordan, James and Agnes were given a slave. The slave was named Green Flake. He was ten years old at the time. In 1843, James Madison joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (also known as the Mormon Church). Green Flake subsequently joined the church in 1844 at the age of 16.

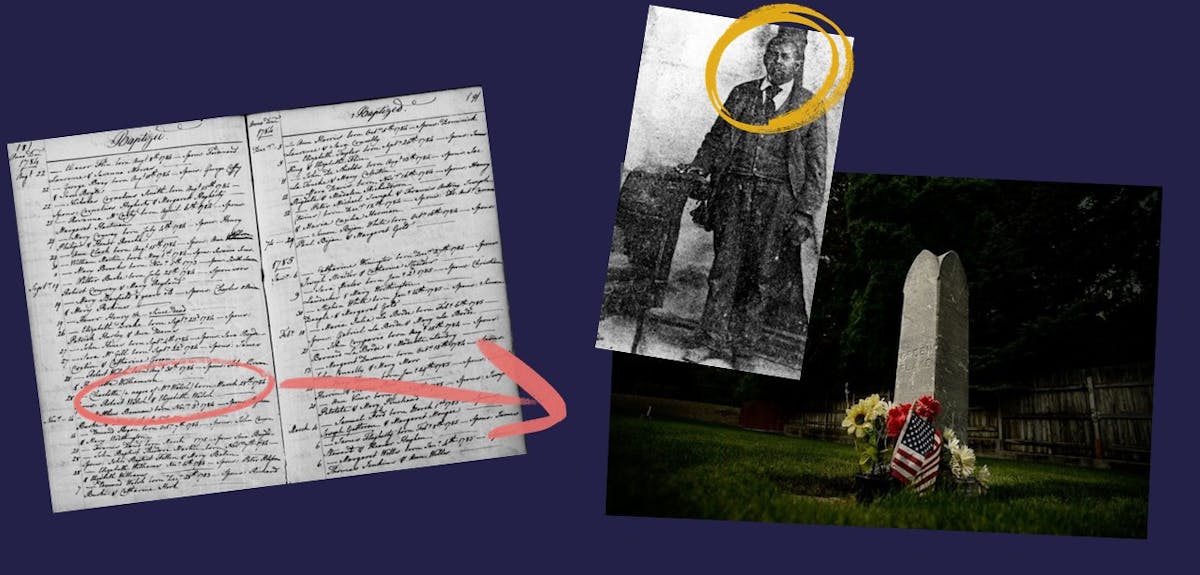

A portrait of Green Flake.

The story of Green Flake is well-documented. We know that after his baptism, James Madison relocated to Nauvoo, Illinois to be closer to the main body of the church, and right before they departed, he freed all of his slaves. It is thought, however, that Green refused to leave the family. His labor was eventually accepted as the family’s tithing to the church.

At the age of 20, he traveled in the first wagon into the Salt Lake Valley and built a home in Cottonwood, Utah. He was treated as both an inferior and an equal by various members of the Church, including Brigham Young.

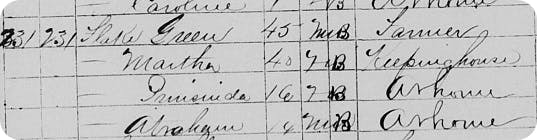

Green Flake and his family listed in the 1870 US Census. View the full record.

Family lore recounts that Green Flake carved his own tombstone which still stands prominently today in the (Fort) Union Pioneer Cemetery approximately 15 miles south of Salt Lake City.

Green Flake’s headstone in the Union Pioneer Cemetery, Salt Lake County, Utah.

I’ve taken my children to this cemetery and told them the story of Green Flake. They looked at me like I was speaking a different language. The idea that someone would ‘own’ another person was a completely foreign concept to them. It gave me an opportunity to explain a painful part of our country’s history, and in this case, a painful part of our family history.

I told them this story as we sat in the Union Pioneer Cemetery in south Salt Lake County standing in front of Green Flake’s headstone. As a family, we’ve learned more about Green Flake and his life and we admire him and his many accomplishments.

When talking about how some of our relatives owned slaves, my 15-year-old son said;

" “that’s so messed up.” "

It was and it still is. But it’s not a story we’ve tried to ignore. I can’t say we’ve totally embraced it but we’ve tried to use it as an opportunity to learn important lessons from the past and apply them to the present, where we still see people who suffer because of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status or other points of difference.

The lasting impact of this part of my family history has made an undeniable impression on both myself and my children, an impact I hope they carry with them for the rest of their lives. But it also creates questions around the variation in which religious bodies addressed (or ignored) the truth of slavery across the United States.

Slavery and religion

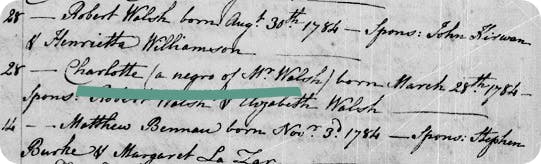

Another example of this can be found in the Catholic Church's sacramental registers. The Archdiocese of Baltimore has published their historic registers as part of the Catholic Heritage Archive, and within the pages, you'll find a number of instances where individuals were labelled, “negro,” “free black,” or “owned by...”. While it was a common practice to have the enslaved join the Catholic church and participate in sacraments, they were still, in the end, regarded as property.

Charlotte was baptised in 1784. A note on her register reads 'A negro of Mr. Walsh'.

In recent years, we've seen more and more research conducted on the topic of religion and slavery. This statement from Albert J. Raboteau's Slave Religion: The “Invisible Solution” in the Antebellum South remains at the heart of the discussion;

"“From the very beginning of the Atlantic slave trade, conversion of the slaves to Christianity was viewed by the emerging nations of Western Christendom as a justification for enslavement of Africans.”"

Across the Caribbean and North America, religious entities like the Church of England and the Catholic dioceses hold these people in their parish registers, congregational records, and minute books. Guides like the Archdiocese of Maryland's Researching Your Black Catholic Roots will help you dig deeper into your family connections.

Still, there are thousands of stories yet to be uncovered. Will you help us discover and tell one?